By Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto

By Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto

My teen learners are amazing. After a long day spent in an environment that values English test scores over communicative skills, they still come to my English class. While they appreciate that pronunciation and word choice matter, and that the best way to improve in English is to use it as a means of communication with their classmates, they have a hard time moving away from focusing on getting right answers. They have enough years of experience as students that they’re generally pretty quick at figuring out patterns so that they can create grammatically accurate sentences, yet still have a lot of trouble in using learned language to communicate meaningfully beyond getting the ‘right’ answer.

I’ve found that giving my teens an audience makes a huge difference. Who they are communicating with helps define language parameters. Trying to communicate something to someone presents students with real-life problems to solve, and encourages them to think deeply about the language they use. Strategic selection of audience and task can help create problem-solving activities that are within my students’ ability to discuss in English. Having an audience tends to help balance the public school focus on English as a subject where success is measured by a test, by focusing on English where success is when communication happens.

Here are three examples where having an audience made a difference.

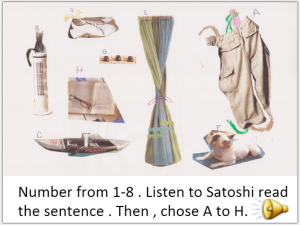

Listening Tests

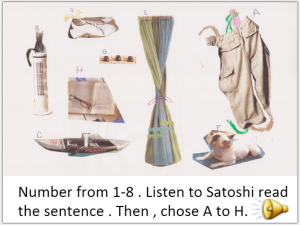

When students answer questions, or talk to each other in class, there’s not much motivation to speak clearly. Even when I ask them to record themselves, they don’t work very hard at careful pronunciation. So, I asked my teens to make listening tests for younger students. The preparation was great review for the older students, but even more importantly, the process of recording the test for the younger students encouraged my teens to make a lot of effort in speaking loudly and clearly. They felt responsible for being understandable. You can hear the effort Satoshi makes in his listening test. Click the link to go to Satoshi’s listening test online, in order to hear his recording.

Book Reviews

My teens do a lot of writing – it really helps them build fluency with the grammar and vocabulary they’ve learned over the years. Even when they write stories where peers are the audience, it doesn’t really push them to consider word choice in the way an outside audience would. So, I had them write book reviews of books they’d chosen to read from our small library. The first time, I asked them to tell me about the book and if they liked it. I got something like this:

It’s a book about dogs. It’s a good book. I like it.

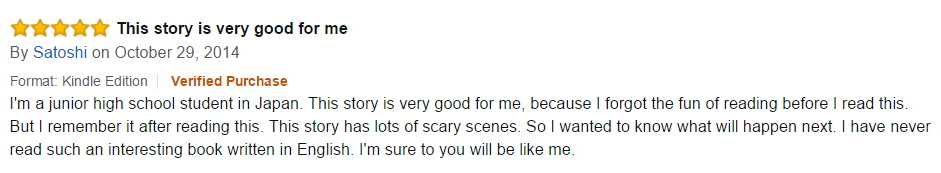

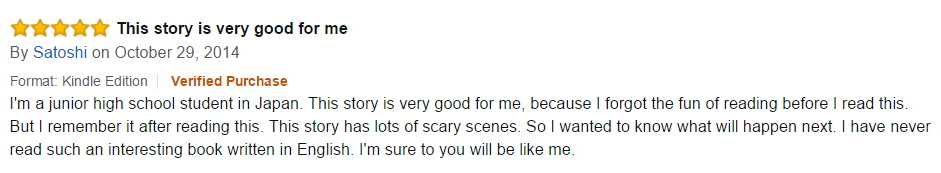

The second time, I told them we’d put the reviews on our class blog so that students in other countries could read them. I told them that their review would help other students decide whether or not they might want to read the same book. Suddenly, they were thinking about what might information might be important to include in their review in order to help other students make good decisions based on their reading interests. They were also being much more careful about revising and correcting, so they wouldn’t look ‘bad’ in public. You can see how Satoshi includes a summary and recommendation in his review.

The third time, we posted the reviews on Amazon. This time we talked about who would be reading the review – teachers, mostly – and why they would be reading it – to decide whether or not to buy the book for their own students. This time I noticed students really considering what information to include in the review based on who might be reading it.

Games

My teens enjoy creating games, and the process can be a great creative and critical thinking activity. However, unless I’m very careful in setting up the activity students tend to switch into their first language when they get caught up in the excitement of deciding content and rules. It’s still a great discussion activity, but not great language practice.

If, however, I ask them to create games for much younger students, the content tends to be language that teens find very easy, and the rules are simple enough that they can manage to keep the discussion in English (mostly, with some reminders).

I asked the students to create a matching card game that would reinforce the language the kindergarten class was learning – shapes, colors, and numbers. They based the first version on a card game they’d seen online (Blink), and then had to decide how many items and how many variations of the items were needed for a game, and then how to adapt the rules so that the kindergarteners could play it in English.

If you’d like to read more about the game students created, I wrote about it on the Teaching Children English blog.

I don’t always specify an audience for tasks, but when I do I find that it helps my students see English as a tool for communication, using it to communicate something meaningful to a specific audience. Success happens when they communicate clearly enough for someone to understand their speaking on a listening test, or provide enough information to enable someone to make a decision, or create an easy-to-play game that reinforces language practice for a specific group of learners. Success in communicating with people outside of their small class also builds confidence in their ability to interact with others, in English.

Over The Wall of Experience

Over The Wall of Experience The Difference an Audience Makes

The Difference an Audience Makes T Stands for Tired Teens

T Stands for Tired Teens

By Marc Jones

By Marc Jones Lighten up! Maybe I am totally wrong here but these young people with their low-level disorder have reasons for what they do. Some of it is about what goes on in the classroom but some of it has nothing to do with school, let alone your lessons. Some teenagers get sleepy because they have heavy workload and social obligations. Question your responses and those of others around you. Are you sure the gamer who is sleepy in every class is not just trying to escape a turbulent home life? Is the noisy kid acting out or is it that there is so much worry at home that there needs to be a release somewhere? We are not always privy to such information so making assumptions seems unwise.

Lighten up! Maybe I am totally wrong here but these young people with their low-level disorder have reasons for what they do. Some of it is about what goes on in the classroom but some of it has nothing to do with school, let alone your lessons. Some teenagers get sleepy because they have heavy workload and social obligations. Question your responses and those of others around you. Are you sure the gamer who is sleepy in every class is not just trying to escape a turbulent home life? Is the noisy kid acting out or is it that there is so much worry at home that there needs to be a release somewhere? We are not always privy to such information so making assumptions seems unwise.