Making The Most of your Classroom – Adam Simpson

The physical challenges of the classroom

Deciding how to plan activities is both incredibly easy and horribly difficult. While we might have a good idea of how we want our lessons to unfurl, perhaps we don’t always give enough consideration to the role of the size and shape of the classroom as we should. While we might recognize that the shape and size of our classrooms dictates how our classrooms are arranged, we also need to understand that these factors should influence our choice of activities.

Before we get down to the business of moving desks and chairs around, we need a clear vision of what the room will look like and how this facilitates the activities we want to use.

The feng shui of the language classroom

Every classroom has a particular energy and flow to it. This isn’t new age mumbo jumbo; it’s common sense. Even in a place such as my school, where a number of rooms all follow a certain design, I find that there are little quirks in the shape and layout which make each unique. The little differences can make or break an activity if you haven’t factored the room into your planning. Here are a few preliminary questions that you might like to ask yourself about any given classroom.

- Do you have enough seats for everyone?

- How mobile is the furniture?

- Where is the board?

- How mobile are you?

- How would you distribute handouts and other materials?

- Are there windows in the room?

- To what extent will the students engage with one another?

If you’ve answered these questions, you’re off to a good start (if, while reading this, other questions came to mind, please feel free to comment). Depending on the answers, you can now approach how you are going to use your room to facilitate learning. You are now faced with a classic ‘either / or’ situation.

1. Making the room work for the activity: Bearing in mind what you want to do in class, you need to think about what adaptations you need to make to the room to best facilitate the outcomes you’re looking for.

2. Making the activity work for the room: If the room can’t be adapted, you need to think about what activities you can do within the constraints that the physical environment has placed on you.

How do you get the room to work for you?

I currently teach in a variety of rooms. Each presents a different challenge in terms of the above questions, but each also presents opportunities to get the room to work in my favour. I’ve given considered thought about what I can and can’t do in each of these environments, and see that they adhere to standard models in the literature. The remainder of this post therefore will be a look at these different models and what activities they facilitate.

1) The dance floor

As the name suggests, the dance floor is a layout that places the focus on an area visible to all. This layout can promote lots of student interaction as all the seats point toward a central focus point. The large, open space in the middle of the room is traditionally in front of where a teacher’s desk might appear and is equally great for group activities and class discussions as it is for teacher talk.

On the downside, that big area might be regarded as a serious waste of space, particularly if you have a large class. Nevertheless, if you’re looking to get a group talking to each other this can be a winner, because students are able to hold eye contact without constantly having to swing around in their seats. However, this seating chart requires a room with a lot of space in it.

2) The catwalk

As I mentioned, I walk around a lot during my lessons, mainly in the hope that my movement will instill motivation in my students, but also so that I can maintain eye contact with each of them and not leave anyone out when it comes to asking questions. The catwalk is effective in preventing me from wandering aimlessly. While it narrows the area in which a teacher can easily move, it’s extremely effective in rooms that have boards on opposite ends of the room. Bear in mind, however, that because you are teaching down the center of the room, you may have the unnerving feeling of being surrounded.

If you’re planning a class discussion or some kind of two-team game, this layout is a practical way of arranging seating, as students will always face the other half of the class. Success with this layout depends on the number of rows you use: the fewer the better. To maximize class interaction, make the rows of students parallel to the center lane as possible.

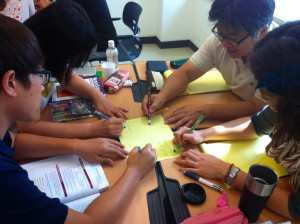

3) The independent-nation-state

If, like me, you see the benefit of cooperative learning, or even if you regularly split your class into groups for games, this layout is a classic. This seating plan instantly tells students that you want them to operate independently from the rest of the class. It’s important that students still need to be able to see the board easily without giving themselves an injury, though.

Using this too frequently can result in a fragmented classroom and a lack of dynamic among the whole class. If your room is permanently set up like this, you eventually find that each group forms their own classroom culture and can’t work with students in the other groups. This is an effective layout, but should not be a permanent one.

4) The Battleship

Like the game, the battleship layout is all about the element of surprise. Consider the picture a metaphor for the battleship, the spirit of which is just to mix things up from the everyday norm.

This layout can be effective when trying to foster creativity, or even the polar opposite; this works when you have to administer a classroom quiz. The battle ship should almost certainly be a single lesson one-off, though.