Ideas and emotions: Finding a space for sharing

Ideas and emotions: Finding a space for sharing

by Stewart Gray.

If you ask me, I’ll tell you: the other teachers working at my current school are seasoned professionals. I believe this is true, but I must admit, I’ve intuited their professionalism from somewhat limited observations and interactions. The unfortunate reality is that the other teachers at my school teach the same chapters of the same books as I do in the classrooms next to mine, and I have no idea what they do in their classes. How do they structure their lessons? Do they have any favorite activities? You’d have to ask them. I haven’t.

I’ve heard teaching described as the “egg-carton profession,” meaning each teacher works alone in their own niche unaware of the doings of others and not sharing what they themselves are doing. Often enough, this description has been about right for my own teaching. In retrospect, I’m horrified by the number of hours I’ve sat pondering a lesson plan in a lonely agony when someone else agonizing over the same material at the same time was a text message away.

It’s not that my colleagues and I would necessarily refuse to discuss teaching practice with each other. It’s rather that, mostly, we just don’t. Why not? Well, on the one hand, I have to acknowledge the role of my own shyness – I’m sure I’m not the only one who finds it hard to reach out. On the other hand, we aren’t encouraged to discuss. At no point in the teaching semester does our employer invite us to share ideas. Indeed, I’ve worked at a few schools, but so far never at one that provided a dedicated space for teachers to express themselves, to advise and support each other. It’s a shame, really, because whenever I have found such a space outside of work, I’ve profited tremendously by it.

Ideas over coffee

A good example of a space I’ve found is the Seoul reflective practice group – a small band of teachers that meets on a monthly basis. What’s wonderful about this group is that it exists for the express purpose of sharing. It represents a private space to hash out our individual professional concerns together, over coffee. We listen to each other and we share our ideas. And it’s really helpful! Over the past few years, my teaching has been shaped and reshaped by discussions I’ve had in those meetings.

I recall, for example, talking with one of the group’s regular attendees, Brian, about difficulties I was having in teaching pronunciation. Brian possesses certain marvellous qualities: he’ll listen attentively to what you have to say, take it all in, then offer his considerable wisdom in a non-forceful manner.* On this occasion, he listened as I vocalised my vexation. I was struggling to come up with any sort of novel, engaging ways to approach pronunciation practice in my classes. As far as I could see, I’d tried everything. Brian calmly absorbed my words and then said, “You know, what I do in my class is I get my students to practice reciting dialogues from short, funny commercials.” And just like that, with that one idea, Brian kick-started a complete rethink of the way I taught pronunciation. It was a good idea. It was a simple idea. I never would have thought of it.

*When it comes to reflective practice, people like Brian are brilliant – find them, if you haven’t already.

Journaling together online, emotionally

For sure, in-person discussion groups can be great. However, they aren’t always possible. Some people might have (or be able to find) compatriots willing to discuss teaching, but they live too far away to meet regularly. For people in such a position, I have a recommendation: create a shared, online Google document in which you and others can all write together. Such a document can be a shared teaching journal, in which everyone can express themselves and offer help to others. This combines the benefits of a private, purposeful, interactive discussion space with the bonus of being largely free of geographic constraints.

I kept such a shared journal once myself with two friends, both teachers, over a period of several months. Each of us would open the journal document each week and write about our “critical incidents” for the week. Naturally, these stand-out incidents would often be challenging and distressing experiences – a conflict with students, feelings of failure at a lesson gone badly, frustration with management, and the like. I remember once after a particularly difficult week, I found myself pouring anxiety out into the journal. I had become angry in class, and though I had tried to hide it, I was certain the students had noticed. I wrote of my crushing embarrassment – I felt painfully unprofessional. And how did my two friends respond to my anxious writings? They wrote back telling me that they understood; that they’d had the same feelings and faced similar situations in their practice; and that I shouldn’t be too hard on myself. Reading their comments, I immediately felt profoundly relieved. I felt supported, not alone. Their empathy, it turns out, was powerful stuff, and it was just what I needed.

The need for sharing

As teachers, we all face challenges. Some of those challenges are practical and might be tackled with some timely advice and inspiration from a peer. Other challenges are emotional. We may experience frustration, self-doubt, fear, and embarrassment in the course of our practice. In such cases, caring responses might be just the remedy. Whatever the nature of the issues at hand, talking things out with other teachers can be helpful and healthy. The alternative, the “egg carton” approach, may mean struggling alone and suffering in silence. It would be lovely if more employers would take it on themselves to provide a space for teachers to talk, share, and support each other. In the meantime, to teachers, I recommend finding or creating such a space wherever, however possible.

So, is it Imposter or Impostor?

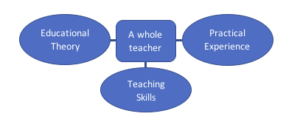

So, is it Imposter or Impostor? Teaching for years in Japan without a recognized teaching qualification or teaching license from Canada always left me feeling somewhat insecure, with a sizeable “gap” in my overall identity as a teacher. Even though I was amassing thousands of contact hours in the classroom, had very good communication skills, continually learned from my many mistakes, and could always fall back on my natural enthusiasm to get students to work with me more than work against me, I always carried a doubt that maybe all of those teachers who earned an actual education degree knew a secret that I, the imposter, would never discover.

Teaching for years in Japan without a recognized teaching qualification or teaching license from Canada always left me feeling somewhat insecure, with a sizeable “gap” in my overall identity as a teacher. Even though I was amassing thousands of contact hours in the classroom, had very good communication skills, continually learned from my many mistakes, and could always fall back on my natural enthusiasm to get students to work with me more than work against me, I always carried a doubt that maybe all of those teachers who earned an actual education degree knew a secret that I, the imposter, would never discover.

Two Conversations About Teaching

Two Conversations About Teaching