Learning English in Indonesia: A Story of a Teacher

Learning English in Indonesia: A Story of a Teacher

by Yitzha Sarwono

English, or what we call “bahasa inggris” in bahasa Indonesia, is something quite natural if not demanding in my life now, because I have been teaching in English for the past 18 years. At the moment I teach kindergarten students, and I use English to do so.

My first experience of learning the English language was interesting, challenging, demanding, and satisfying. My education in English began at home with my late grandfathers. One of them was a columnist in a women’s magazine, where he wrote articles based on stories around the world. To do that, he had many books in English. He was the first person who taught me to read at the age of four, because I demanded that (in a cute kind of way). He would bring Donald Duck comic books written in English and I would make sense of the story before I was able to read it. We both liked to do roleplays. I was really keen on becoming a news anchor back then, so reading was on my list of things to do because I wanted to be able to imitate those TVRI channel news anchors with their white papers and glasses. My other late grandfather spoke Japanese, Dutch, and English very well because he worked at a government hospital. He used to teach me songs in those languages.

My late Papa was also responsible for my education. He used to collect cassettes with foreign music and I listened to songs from The Osmond’s, Queen, Sting, and many more. I loved reading the lyrics on the back of the cover while listening to the songs. My Papa sometimes would cover the lower part of our black-and-white TV during shows like “Little house on the prairies” or “Daktari” with white paper so I would focus on the story and listen to the actors rather than spend time reading the subtitles. Sometimes that was tough, but I got used to it in the end. Therefore, the three men in my early life were responsible for imparting the education of the English language to me. I consider it as a blessing to have been born and raised in that environment.

My first experience of learning English at school

After going through a very lovely childhood, my first steps in learning English at school started at the age of 12 when I entered junior high school. I remember the first day of lessons quite well. My teacher then, Ibu Euis, entered the room and said, “Point to the board!” Most kids were confused but I knew what I had to do. I stood up and held out my finger to point to the board. Pretty soon other kids followed me when Ibu Euis said that I was correct. She then asked us to stand somewhere, take something, and ask each other to do something. Since then, English became one of my favourite subjects, along with history and biology. As a junior high school student, I was taken to a new level in learning English. I remember writing short simple texts, such as stories and poems. I wasn’t always good at grammar but I did quite well in speaking and writing. In high school, I remember constantly getting 6 or 7 points out of 10 during grammar tests. Still, being an English teacher wasn’t one of my plans, even though I did tutor a few of my friends on the subject.

The difficulty of learning English rules

There are many differences between bahasa Indonesia and English that made the learning quite difficult for me.

- Grammar holds the key! Most of the tests at school were about grammar. The English grammar was treated like physics or maths and you had to memorize the pattern: for example, Simple Present = Subject + Verb 1, or Present Continuous = Subject + be + Verb-ing, etc. Sometimes it was a bit frustrating because instead of writing or answering questions, the test would be about writing the grammar pattern! In this way, instead of understanding the principles, we were forced to learn only the formula. I know many of my friends hated English because of it.

- Alphabet and phonics. In bahasa Indonesia, there is no phonetic way to read letters. Letters will sound the same when you spell them and say them. In English, as we know, it isn’t the case. Letter “C” is read as /s/ in the alphabet but as /k/ in phonics. Besides, there are many rules that can give letters different sounds (such as digraph, long vowel, short vowel, consonant cluster, and so on). For Indonesians, it’s confusing to learn that you read “cup” as \ˈkəp\ but “put” as \ˈpu̇t\ – when they both look almost the same in writing… I didn’t have proper English spelling lessons back then so we were taught to memorize how something is written instead of understanding the sounds and ways of spelling them out. It was not until around year 2000 that phonics was introduced in curricula and studied to help students learn to read. So back then, reading for me was all about how I felt it should sound rather than spelling it phonetically.

- The shapeshifting verb! In bahasa Indonesia, verbs stay the same no matter what time you are referring to. In English there are three verb forms, there are regular verbs and irregular verbs. It can all be a bit confusing sometimes. I remember having many tests back in high school that focused entirely on writing Verb 2 and Verb 3. Again, it requires memorization and it’s not always easy.

- Gender in the subject. There is no “he” and “she” in bahasa Indonesia, so I often make a lot of mistakes when it comes to subject pronouns, especially when they are used directly in conversation. I’m getting better but still, mistakes are occasionally made.

At a later stage, I began learning the fundamental concepts and rules of English grammar. I gained a fairly good understanding of the points I mentioned above. As I moved up to university, I learnt how to use interesting expressions to write short stories and poems persuasively. Apart from this, I was also exposed to learning more advanced rules of grammar. I must mention that my English reading and writing skills were tested during this time as I started to have pen pals whom I could practice English with. This helped me to see my confidence grow as I replied to questions in English.

Books, conversations, and films for learning English

My parents instilled in me the habit of reading. When I was 13, my late grandfather gave me the hardcover version of “The Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens, because I had just seen Oliver Twist TV series and told him I wanted to know more about Charles Dickens. As a result of reading a lot of books, I was able to increase my vocabulary and develop writing skills. In addition, one of the most important English learning activities for me has always been conversation. I started speaking English with my sister, my father, and a few school friends. The experience of conversing in a foreign language was precious to me as it improved my communication skills. Watching TV, particularly TV series, has also always been an enjoyable learning experience for me. I learnt many kinds of phrases, jokes, puns, and even sarcasm from watching them.

For the most part, learning the English language has been an interesting journey for me and I am still trying to achieve a certain level of proficiency in English. I can’t say it has always been easy, but I suppose the difficulties are all part of it. One thing I notice, though, is that I do behave and act differently based on the language I speak: I’m very calm and patient speaking Javanese (my second native language); I’m quite loud, goofy, and fast as a bahasa Indonesia speaker; I’m rather serious and blabbery when I use English. There is something about the language itself that drives me to act in such a way, I suppose. Nevertheless, my journey in learning English shall never stop as there is always something fascinating about it that I can find when I dig deeper.

A Day in the Life…

A Day in the Life…

Learning English in Israel

Learning English in Israel Learning English in Indonesia: A Story of a Teacher

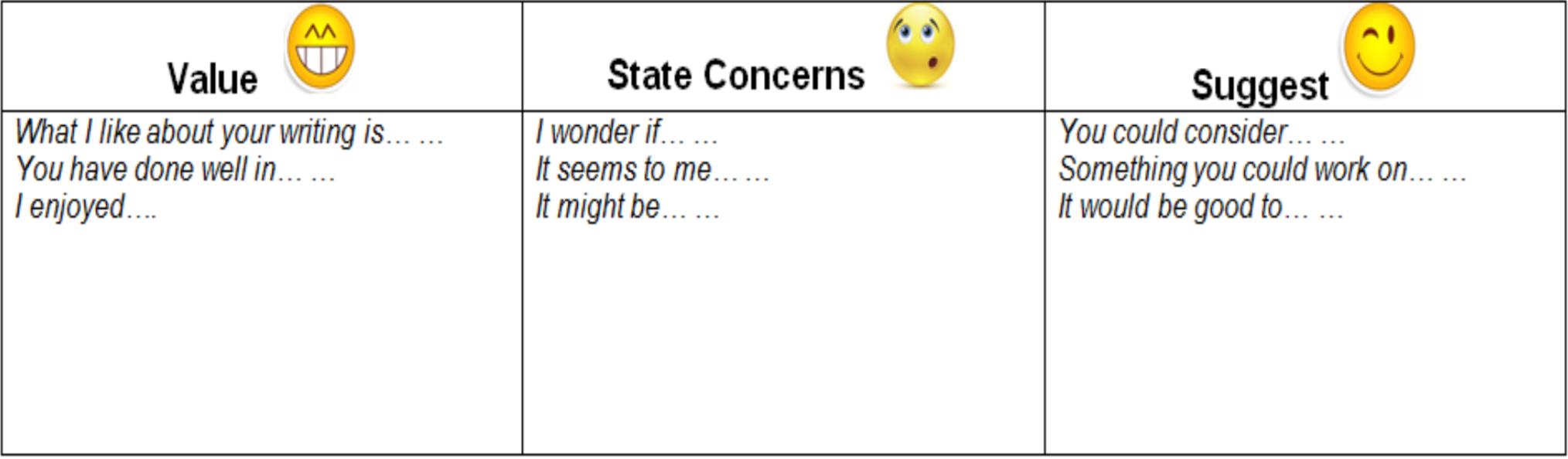

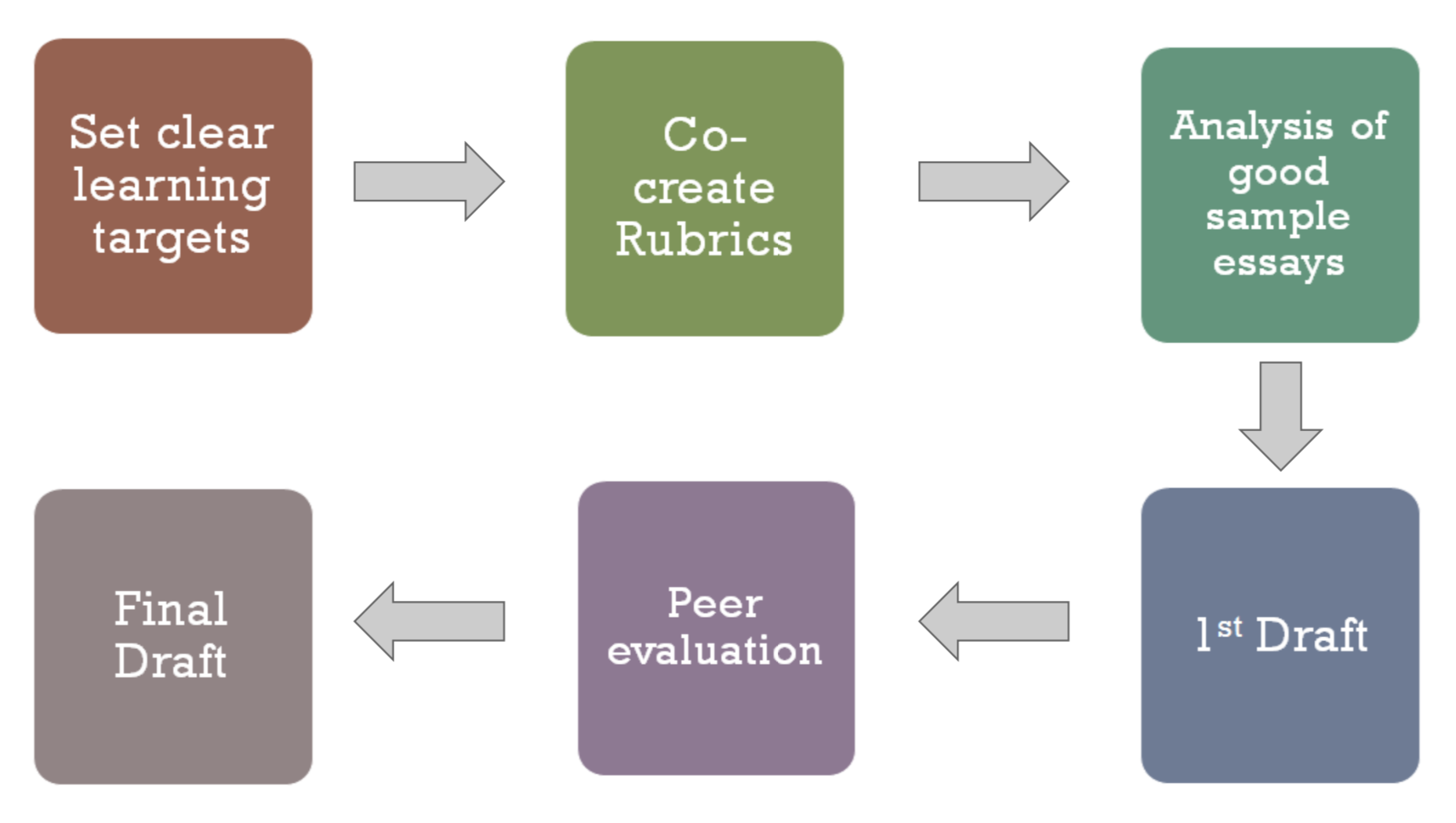

Learning English in Indonesia: A Story of a Teacher Learning about Peer Evaluation in Singapore

Learning about Peer Evaluation in Singapore