Learning about Peer Evaluation in Singapore

Learning about Peer Evaluation in Singapore

by Eunice Tan

Disclaimer: The diary page below was written by a teacher and cannot be said to contain 100% accurate reflections of a Singaporean student learning English.

It’s time for our daily English class again. While it’s not like I dread learning English, I sometimes think I am not improving at all. Not my teacher’s fault I think – she’s nice! But being in Secondary One this year means that there’s a big difference from the way we learn English now and the way I used to learn it in primary school. Hopefully it’s because of this new learning environment and not me.

We’re working on writing emails again today and Ms. T is introducing something called peer feedback. I think it means my friends are going to *gasp* READ MY WRITING!! Also, something I’ve been thinking since she first taught us about emails… Who writes emails anymore? Will I really need to write something like that when I start working? Why can’t we just Instagram or Whatsapp our colleagues? Ok fine, Ms. T says we’ll be practising writing emails to our Principal and I guess talking to the Principal through Whatsapp is a little strange. Email it is.

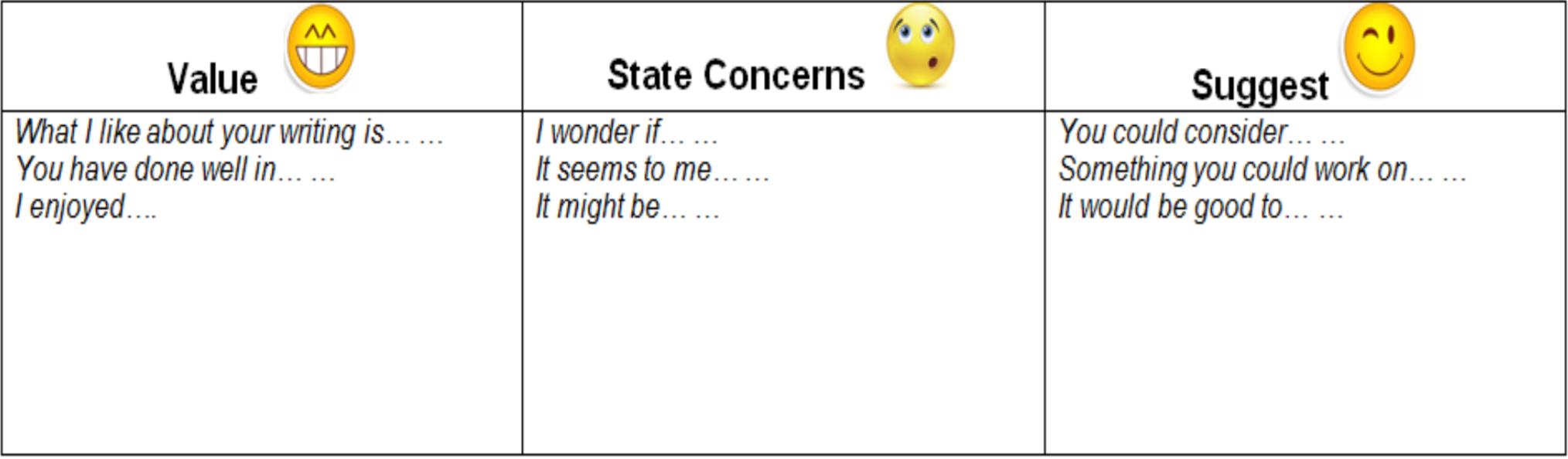

Anyway, Ms. T is telling us not only do we have to read our classmates’ emails, we have to give feedback on the email we’re in charge of. That’s fun! I totally know how to give advice, so I’ll be good at giving feedback I think. Oh wait, now she’s saying she’ll show us how to give feedback. Alright, let’s see… She’s talking about Daniel Wilson’s (who is this guy?! Maybe he has Instagram…) Ladder of Feedback and first we have to Clarify, then Value, then State Concerns and lastly, Suggest. OMG, this is impossible. Can’t I just tell my friend if I like the email or not? Oh alright, she’s giving us some help. Help is good. Very good.

I guess those helping words are kind of useful. Giving feedback using the table like this is going to take some time though, but it makes me feel more useful and I get to do more than just write emails! Maybe that’s what Ms. T means when she says she wants us to be more engaged and take ownership of our learning. I really wonder though, if the comments that I give will help the person, and if I can give accurate comments… also, since my classmates are my peers, it’s going to be quite difficult to give extremely honest feedback because some people may take it personally.

Anyway, let’s try this. I’m excited to see what feedback my classmates give me…

Who do you write for? Why do you write? For some time now, peer assessment has been used in Singapore public schools to communicate the idea of writing for an audience (other than the teacher). Recently, coupled with Jan Chappuis’ strategies for assessment, some Singaporean teachers are also finding out answers to questions like these: How do you know which areas of writing students need to improve in? How can we help students improve in those areas?

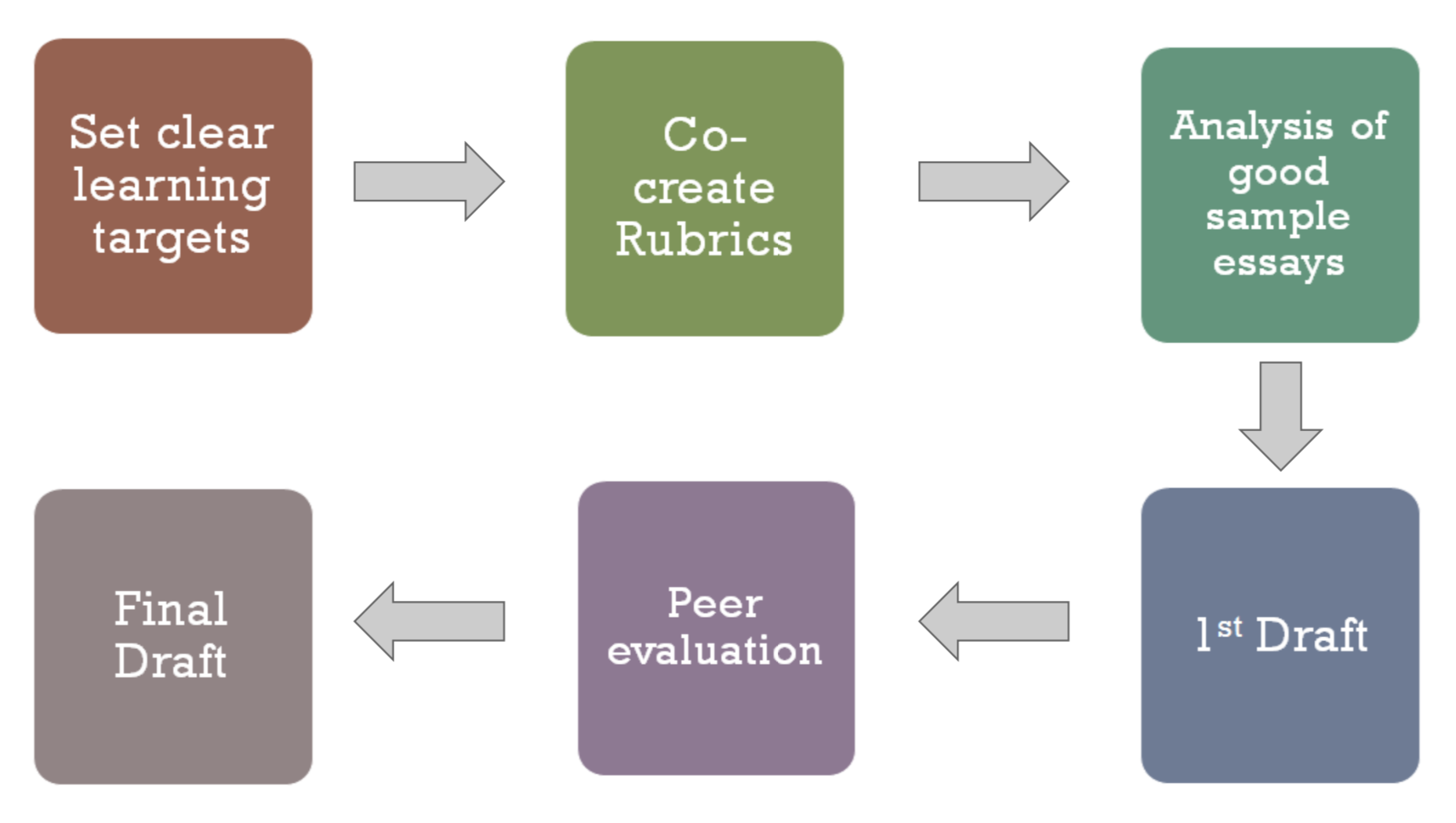

In a Singapore secondary school, a group of English teachers took a systematic approach to peer assessment through the use of rubrics and teacher modelling. Some classroom activities carried out included editing the rubrics commonly used by teachers to feature student-friendly language for student use, teacher demonstrations using strong and weak examples of writing, and peer feedback, which is the focus of this post.

Peer feedback was the teachers’ way of applying one of Chappuis’ strategies in helping students to improve their writing – guiding students to identify their current skill level. According to Chappuis, this can be done by “offering regular descriptive feedback during the learning.” By teaching students how to carry out peer feedback, the teachers are aiming for students to develop as self-regulated learners.

At the end of this project, the teachers learnt four things about how students could improve their English writing skills. First, clear learning goals have to be set, what students are expected to write should be modelled, and scaffolding students in peer evaluation is necessary. Lastly, for this systemic approach to peer assessment to work, both students and teachers should have ample opportunities to familiarize themselves with the process.

*The project described above was a huge undertaking by a particular Singapore secondary school and as such, names of the teachers and students could not be provided. For more information, please contact the author and if possible, she will put you in contact with the teachers who led and participated in the project.

References

Chappuis, J. 2015. Seven Strategies of Assessment for Learning, 2e. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, pp. 11-14.