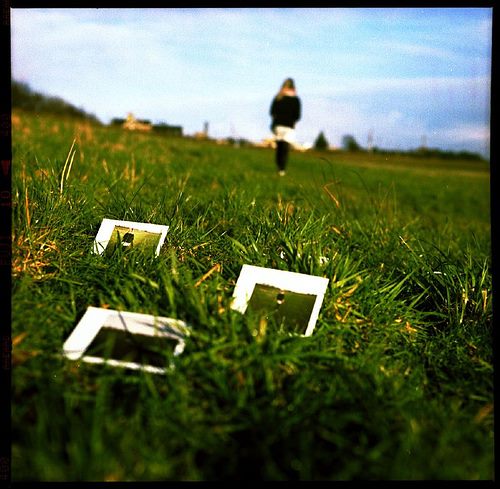

In April, the beginning of a new academic year in Japan, I will be leaving my current teaching position and moving on to another. I currently work on the program focused on developing learners’ oral fluency skills through topical discussions. Although the teaching context in my next job is similar, and the country and city the same, the transition process will put me into an unfamiliar situation. However, I take comfort in knowing that I have the options and ability to take with me lessons and experiences learnt from my current teaching post and leave behind some less useful things. In this post, I will give a brief summary of a reflective conversation I recently had with some of my fellow peers who are also moving on to pastures green, reflecting on our keepsakes from our current job and items that we wish to leave behind.

Taking Effective Classroom Practices

Unanimously, we all agreed that we would like to take with us elements of effective classroom practice, or at least what we think that to be. Firstly, something that we have all learnt to do in our current teaching positions is keep target language input manageable in each lesson, and make classroom expectations explicit and achievable for all students through a combination of tasks and instructions. Looking back at previous teaching jobs, we thought about the amount of lexical items, language functions and/or grammatical features that we once brought to our learners, as well as our approaches to language use and practice in our classes. We felt that, in moving from one teaching job to another, there are very few reasons why this ethos cannot be continued and maintained, and that we would like to keep favouring quality of learner output over breadth of input.

Taking Elements of Classroom Management

We also reflected on our institution’s approach to using English as the sole medium of instruction. Although this practice is often contested and debated in the related research literature, my colleagues and I mostly shared the feeling that learning and language development can be successfully achieved through this means. Finally, some of the group reflected on how disciplined they had become in intervening less when communication breakdowns occurred between learners, and instead opted to leave space for negotiation of meaning and understanding between learners themselves before giving any explicit support. We additionally felt that as the years went by in our current teaching position, we all spoke less in class and vastly economised our teacher talking time, which we felt was to the benefit of our learners.

Taking the Ethos of Unity

We will all be leaving a unified program, a program where multiple instructors not only develop and teach the same lesson content to various groups of learners, but work together to ensure a consistent and equitable learning experience. Although this sense of togetherness will be missed and may not be revived in our future teaching roles, we all felt that we would like to continue to strive for unification with our new colleagues, trying to quell any potential disparity in assessing students and reach common agreements on curricula goals.

Leaving Behind Constraints

It was hard for our group to think about what we would like to leave behind as it was a lot easier and much more fun to reflect on what we would like to take forward with us. However, something that was continuously mentioned was the word constraints. Although leaving a unified program will leave us feeling slightly exposed and somewhat directionless, we also agreed that we will also feel less constrained in some respects and be able to operate more autonomously as teachers. In working within a unified curriculum, it is not always possible to teach exactly the way one wants to, deviate a great deal, or make wholesale adaptations. We are therefore looking forward to being potentially re-acquainted with teaching approaches that we have all come unaccustomed to over time, things like working with vocabulary, project work, reading and writing skills. We are prepared to set a variety of homework activities, something we never thought we would find ourselves saying. We are happy to be leaving behind the rigid pacing of our lessons and relative inflexibility of the curriculum. We will no longer feel pressured to complete elements of our lessons within a given timeframe, and instead will look to build in more flexibility with timing where possible and necessary.

Leaving Behind Past Identities and Roles

Finally, we all reflected on our changing roles and identities as educators entering new positions. Some of us are happy to not feel an expectation or burden to conduct research and write articles, while others are looking forward to the greater scope and freedom to such activities. Some of us are happy with shifts in focus, such as moving from being a language teacher to a content-integrated language teacher.

I hope I could show with this post that moving from one job to another gives teachers a chance to reflect on both positive and negative aspects of a teaching position and consider what experiences can be left behind and what can be packed up and taken with. If you and others around you find yourself in a similar position, why not take the time time to come together and talk through this transitional process collectively? Your shared experiences from one job can create a more comfortable bridge into a new stage in your teaching career.