By Chris Mares

By Chris Mares

‘Reflective Practice’ is a familiar term to many teachers. It has a positive connotation and intuitively seems like a good thing to do. But what is it really, and how do you do it in order to become a better teacher? These are both interesting and important questions.

The first point is that reflection is more than simply thinking. There needs to be a critical, analytic quality to the process and the results of any meaningful reflection need to be articulated thoroughly. More precisely, reflection needs to be ongoing, purposeful, rigorous, and systematic. It also needs to have an outcome that informs our teaching.

Like all skills, ‘reflective practice’ takes time and organization. I will suggest an approach that will model how reflective practice can be done. This approach should be seen as an example only as there are other ways that would be equally valid.

The Premise

The premise underlying reflective practice is that you are prepared to take an ongoing systematic look at what you do as a teacher, you are prepared to critique yourself honestly, and that you are prepared to modify or change what you do and how you do it in order to be a more effective teacher. For this to be a productive experience, you have to want to do it and not be afraid to confront aspects of yourself and what you do that might at times be unsettling.

For the sake of this post let’s simply assume that all teachers want to be better teachers.

Focus

One strategy is to focus your reflection on a particular aspect of your teaching, for example, how you deal with student errors, how you give instructions, how you approach grammar, or how you raise schema. An accompanying requirement is to develop a list of rigorous questions that will take you to the core of what you are focusing on. All teachers are familiar with the visceral responses, “that went well” or “that didn’t quite go according to plan.” These are acknowledgements of what appeared to happen rather than critical reflection. Rigorous questions are ones such as, “Did I raise student schema before the activity?”, “Were my instructions clear and effective?”, “Did the students achieve the goal I had set for them?” These questions provide you with useful and focused answers about what happened. Essentially, they will result in data that can inform your teaching. Leaving a classroom with a feeling that the students had fun or that they seemed bored does nothing to explain what happened or whether your goals were achieved. On the other hand, principled reflection does.

Record

Asking rigorous questions that get to the root of both your teaching and your students’ engagement and achievement is just the beginning of the process. The next stage is the recording of these reflections. I like to keep a journal in my bag which I use for making notes about what I have done in class. I also use it to make quick reflective notes that I later type up and store electronically. The process of writing by hand and then typing both allows for the possibility of refining and building on the initial thoughts you had when you began your reflections.

Review and Implement

Having gone through the process of teaching, reflecting, and then writing up your reflections, it is necessary to review what you have written. Over time you will begin to notice patterns and detect preferences. Sometimes you will learn from what you have written specifically. At other times you will learn from what you have not included. For example, if you notice a sameness in your teaching, you will learn that you don’t often experiment with new techniques or activities.

Reflective practice when carried out thoroughly is an excellent way to get an accurate sense of what you actually do in your classes, not just what you think you do. It also allows you to see patterns and possibilities, and to learn about your teaching style and activity preferences.

Conclusion

Reflective practice requires meaningful disciplined reflection over time. In this way it becomes a practice. If approached positively and with purpose, it also becomes a means of exploring your own threshold for honesty and self-examination.

And, as we all know, a life is only meaningful if it is examined.

By Zhenya Polosatova

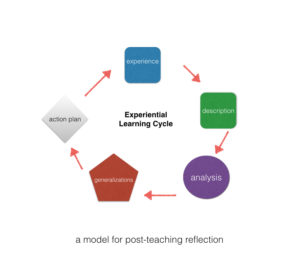

By Zhenya Polosatova Reflective Practice is often associated with and is a part of Experiential Learning, or ‘learning by doing’. This approach emphasizes the importance of trying things out and learning from that experience. Interestingly, life itself can be seen as “the experience of being alive” if you check the definition in a dictionary.

Reflective Practice is often associated with and is a part of Experiential Learning, or ‘learning by doing’. This approach emphasizes the importance of trying things out and learning from that experience. Interestingly, life itself can be seen as “the experience of being alive” if you check the definition in a dictionary. I like the simplicity of this model: it never takes too long to explain or demonstrate to readers, teachers on a training course, or colleagues. What I find interesting about seemingly simple things in life is that applying them in practice takes much more time and effort than learning the theory. For example, have you ever tried describing an event, to the tiniest detail, without adding your own feelings to what actually happened, without expressing your opinion or attitude to it? If you have done so before, you know how hard it might be not to switch into interpreting what happened rather than simply describing it. If you have not, select a moment of a lesson that stands out to you, describe it in writing (or audio record yourself), then take a look and see if this was a description or… not.

I like the simplicity of this model: it never takes too long to explain or demonstrate to readers, teachers on a training course, or colleagues. What I find interesting about seemingly simple things in life is that applying them in practice takes much more time and effort than learning the theory. For example, have you ever tried describing an event, to the tiniest detail, without adding your own feelings to what actually happened, without expressing your opinion or attitude to it? If you have done so before, you know how hard it might be not to switch into interpreting what happened rather than simply describing it. If you have not, select a moment of a lesson that stands out to you, describe it in writing (or audio record yourself), then take a look and see if this was a description or… not.

By Stewart Gray

By Stewart Gray