Six Words about Teaching English in Ukraine

Six Words about Teaching English in Ukraine

by Zhenya Polosatova

Ukraine is my home country, it’s where I was born, raised, and had all of my EFL learning and teaching experience. I taught English as a foreign language to kids and adults at IH school (International House DNK) for about ten years. My youngest student turned two in one of my lessons. Even though I have not been teaching on a regular basis lately, I consider myself a part of the ELT family as I am actively involved in teacher training (intensively internationally and online), facilitating/coordinating a Reflective Practice Group in my native Dnipro, and co-organizing EduHub Teacher Sharing Days. I also do some consulting, coaching, speaking examining, and presenting in various places in Ukraine.

I am aware I am far from being an ideal person to speak about the Ukrainian ELT. On the other hand, not being directly from (or attached to) a particular sector of the Ukrainian ELT field may offer a chance to step back and catch a bigger picture. The ideas I express in this post come from my own experience and reflections, as well as numerous conversations with teachers of English throughout Ukraine, such as former colleagues and TESOL course participants, Reflective Practice Group members, conference presentation attendees, small language school owners, teacher educators, “international” teachers, etc. As anything I say in this post can be seen as overgeneralizing, I chose to structure it around six words that can describe my views on ELT in Ukraine.

#1: Transformation

Let’s start with the name of the country: it is Ukraine, not the Ukraine. There is an idea that “the use of the article relates to the time before independence in 1991, when Ukraine was a republic of the Soviet Union known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.” It is a seemingly small thing, but to me it symbolizes the change we are going through from being a part of the USSR to finding our own identity.

Ukraine is a large country in Europe spreading over 603,628 square km. Ukraine’s regions and even cities differ a lot from one another: teaching and living in Kyiv, the busy capital, would be different from Lviv in the West, Odessa in the South, or Dnipro where I am from. Ukraine’s ELT context is therefore quite varied. Working in the public school sector would be different from teaching in a private school, having a contract with a language center is not the same as freelancing, and freelancing in a large city would certainly be different from doing it in a small town.

In addition, it’s important to note that Ukraine outsources IT specialists throughout the world, which results in (1) excellent Internet connection across the country and (2) the demand for English teachers, especially in large cities. This fact adds another significant ELT context to work in – a full-time teaching job with an IT company.

#2: Application

Even though English has been the leading foreign language taught on each educational stage (optional at pre-school, but mandatory from primary school), it started to play a much more noticeable role after 1991. Teaching switched from mostly Grammar-Translation Method to more progressive approaches and techniques, new coursebooks entered the market, international training courses for teachers were offered, private language schools were opened.

Gradually, state school sector opened its doors to international publishers and course providers and approved a number of international coursebooks, exam results, and teacher training qualifications. Even though we may discuss advantages and disadvantages of teaching from a coursebook or using grammar-based syllabi as opposed to Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), for example, I personally see the change as positive as students get to use the language in the classroom more and more (and potentially apply it outside, “in real life” as well).

The educational reform called the New Ukrainian School started in 2017. It is bringing even bigger changes in attitude to language learning where “communication in foreign languages” becomes a goal, a competence/skill set to develop, “the ability to understand adequately concepts expressed in a foreign language, to express both in speech and in writing the ideas, thoughts, feelings, facts and views” (from Conceptual Principles of Secondary School Reform).

English in Ukraine is still a foreign, not a second language, although you can encounter it more and more in the large cities, tourist centers, movie theaters, book stores, etc. Sadly, the level of English proficiency among Ukrainians is low, taking 28th place out of 32 European countries according to the EF Education First annual ranking.

#3: Motivation

It could be a big generalization to make, but working with the Ukrainian language learners (adults or young learners) is wonderful: their curiosity, open-mindedness, optimism, and sense of humor are amazing and energizing. As my colleague and friend recently told me, “I love our job as I am paid for this kind of interaction [with my language learners].”

At the moment English learners here are very motivated and goal-oriented, both short-term and long-term. Many would like to study or work abroad, some need high language level at the current job communicating with an international partner or customer, and some are actively traveling. International testing systems and exams are gaining popularity in the country, which often becomes a measurable sub-goal students would like to reach.

#4: Enthusiasm

Goal-oriented students (and their parents!) are demanding, and this motivates teachers to do their best. I can say that most ELT teachers in Ukraine are passionate, eager to help kids and adults, ready to learn, trying to perfect in the skill of teaching. They are able to bring life and passion to sometimes unrealistic or boring curriculum. In the light of the educational reforms, I think teachers of English are at an advantage today, being able to have direct access to lots of resources, ideas, activities, and social media platforms internationally.

To give an example, while looking for ideas for this post, I learned about a teacher in a small Ukrainian village near Dnipro who has been successfully engaged in eTwinning Plus project collaborating with schools in other countries and engaging students in exciting and motivating activities in English (there is an article about Yaroslava Kazarian’s project in Ukrainian here). Another colleague from Kyiv, Olga Puga, co-created an online School of Magic, similar to the school Harry Potter attended (more in Ukrainian here). To me, these are good examples of “enthusiasm in action” and they are inspiring.

#5: Choices

Overall, I think it’s very interesting and exciting to be an English teacher these days. You have the Internet, access to ELT materials and webinars, you can decide what kind of international training certificate to earn and do it in Ukraine. One of the big changes the reform offered is a choice, where state school teachers can earn the number of obligatory professional development hours (it used to be possible only through designated centers of “enhanced qualification” and those courses often left much to be desired in terms of format and content).

Since 2017 Ukrainians can travel to EU without a visa, which literally opened doors to international ELT events. My colleagues have recently attended and/or presented at conferences in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia, and more trips are planned for the coming spring (Spain, Malta, Moldova).

There are teacher development events to attend in various cities in Ukraine. Apart from large conferences, such as IATEFL Ukraine, and training workshops from publishers, there are smaller events offered by specific training centers or even teams of teachers. The so-called “non-conference” ELT events are becoming popular, for example EdCamps (educational camps) and reflective practice discussion groups for teachers. These are face-to-face, “real-time” events, and there is a whole different dimension of webinars, online courses, social media groups available. I would say that there are too many choices and sometimes a bit of free time is needed – to breathe, to think, to do nothing.

Besides, living in the times of constant change has made teachers here even more hard-working, resourceful, and flexible, and that includes their attitude to employment. Many colleagues I know have recently become freelance professionals, probably following what we call a Ukrainian characteristic feature of wanting to be fully in charge of a small business, but most likely using their creativity and teacher-preneurship skills to build a career of their dream.

#6: Journey

There is a well-known wish often seen as a blessing or a curse: “May you live in interesting times.” While there is no choice in what time we can be living, we can certainly manage our attitude and goals. As our famous poet Taras Shevchenko* put it addressing his fellow Ukrainians, “Gain knowledge, read, from other cultures learn! But do not thus neglect your own.” I think Ukraine as a country, and ELT in Ukraine as a field, is at the beginning of a big journey to discover what’s important, to learn from the modern research and practices, and adapt it to the local culture and needs.

Questions to the readers:

- What is special/unique about your country? How does (might) this impact learning and teaching English there?

- What would be your 6 words about teaching English in your country?

- What do you dream about for ELT in your context in the future?

- What change do you want to see happen?

- What small steps can you personally make (or are already making)?

Links:

- Wikipedia: “In 1993 the Ukrainian government explicitly requested that the article be dropped.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Name_of_Ukraine#English_definite_article

- Mining Academy in Dnipro, EFL Magazine. https://www.eflmagazine.com/where-i-teach-in-ukraine/

- Olga Afanasieva in Cherkasy Uni, ET Forum. https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/etf_55_4_36-40_title__my_classroom_-_ukraine.pdf

- The Internationalisation of Ukrainian Universities: the English language dimension, by Rod Bolitho and Richard West, British Council report. http://www.britishcouncil.org.ua/sites/default/files/2017-10-04_ukraine_-_report_h5_en.pdf

- Kris and Kate’s blog offers a different perspective on living and teaching in Ukraine, e.g. Teaching English in Ukraine: A Guide. https://whatkateandkrisdid.com/teaching-english-in-ukraine-a-guide/

- National Conference “eTwinning Plus” in Ukraine (May 2018, Kyiv). https://erasmusplus.org.ua/en/37-news/2096-national-conference-etwinning-plus-in-ukraine-21-05-2018-kyiv.html

* from Shevchenko’s “My Friendly Epistle,” written in December 14, 1845.

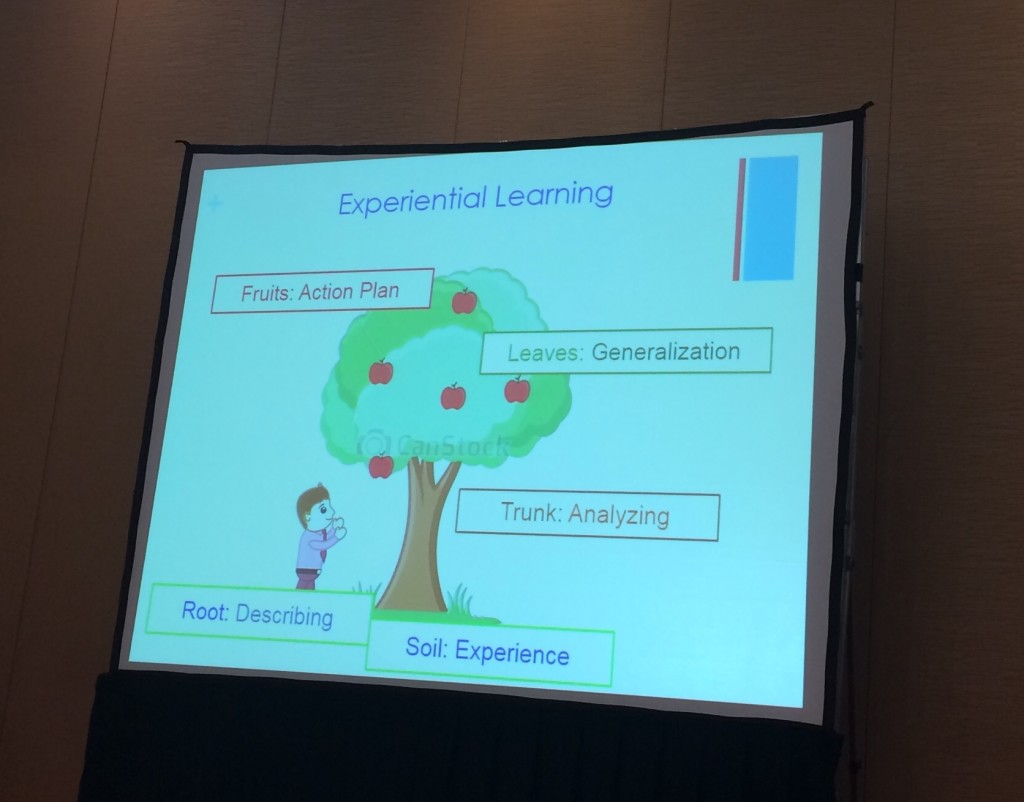

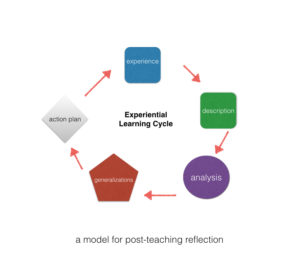

Reflective Practice is often associated with and is a part of Experiential Learning, or ‘learning by doing’. This approach emphasizes the importance of trying things out and learning from that experience. Interestingly, life itself can be seen as “the experience of being alive” if you check the definition in a dictionary.

Reflective Practice is often associated with and is a part of Experiential Learning, or ‘learning by doing’. This approach emphasizes the importance of trying things out and learning from that experience. Interestingly, life itself can be seen as “the experience of being alive” if you check the definition in a dictionary. I like the simplicity of this model: it never takes too long to explain or demonstrate to readers, teachers on a training course, or colleagues. What I find interesting about seemingly simple things in life is that applying them in practice takes much more time and effort than learning the theory. For example, have you ever tried describing an event, to the tiniest detail, without adding your own feelings to what actually happened, without expressing your opinion or attitude to it? If you have done so before, you know how hard it might be not to switch into interpreting what happened rather than simply describing it. If you have not, select a moment of a lesson that stands out to you, describe it in writing (or audio record yourself), then take a look and see if this was a description or… not.

I like the simplicity of this model: it never takes too long to explain or demonstrate to readers, teachers on a training course, or colleagues. What I find interesting about seemingly simple things in life is that applying them in practice takes much more time and effort than learning the theory. For example, have you ever tried describing an event, to the tiniest detail, without adding your own feelings to what actually happened, without expressing your opinion or attitude to it? If you have done so before, you know how hard it might be not to switch into interpreting what happened rather than simply describing it. If you have not, select a moment of a lesson that stands out to you, describe it in writing (or audio record yourself), then take a look and see if this was a description or… not.