Kevin Stein – Japan

Kevin Stein is the coordinator of the International Course at Clark Memorial International High School Osaka Campus. He believes that a classroom is a place for teachers and students to learn and grow together. He lives in Nara, the ancient capital of Japan, and often spends Saturdays feeding deer with his daughter. When he is not feeding deer, he can often be seen making up silly songs and dances with the other members of his family.

Kevin Stein is the coordinator of the International Course at Clark Memorial International High School Osaka Campus. He believes that a classroom is a place for teachers and students to learn and grow together. He lives in Nara, the ancient capital of Japan, and often spends Saturdays feeding deer with his daughter. When he is not feeding deer, he can often be seen making up silly songs and dances with the other members of his family.

What are you passionate about, Kevin?

When I was younger, I was passionate about understanding things and getting them right. For about six years, I was a social worker in Chicago and I just loved to read psychiatry and psychology and social work journal articles. They seemed to me to have the answers I was looking for at that time, and I would be lying if I said I didn’t get a whole lot out of them. From how to handle basic mental assessments to things like how to use mirroring to help set a client at ease, the articles were filled with good information. And when I started teaching English in Japan 13 years ago, with a master’s degree in creative writing and very little ELT training, I also felt like theory would be a great way for me to make sure I was doing the “right thing” in class. But recently, they way I look at my role as a teacher has changed. Or perhaps it has been changing and recently I’ve really noticed this change playing out in how and what I teach. Now I am passionate about finding out from my students what they need. I realize that they are more than willing to let me know, if I am willing to take the time to notice. And while I still love to read journal articles, I have to admit that the longer I teach English, the less sure I become of even the most basic terminology such as EFL or communicative learning. A lot of the energy and love I had of theory has become a passion for how students and I can work together to find a path which helps students attain their goals. In the same way, I think this outlook on teaching has informed how I relate to my coworkers and even my friends and family. I guess I don’t feel like I have any answers, but I’m happy to spend time and energy thinking about any number of questions and seeing what I and the people around me can come up with together.

How and why did you become a teacher?

I actually taught my first language class when I was 12 years old. I was preparing for my Bar Mitzvah, a Jewish coming of age ceremony, and I was practicing reading and chanting Hebrew as I had to recite a portion of the Old Testament in Hebrew. As part of my training, I was also expected to teach some basic Hebrew lessons to the kindergarten students at my temple. I watched one of the older, more experienced students lead a class first and then it was my turn. It was very communicative based. We would just say phrases to the students and kind of expect them to answer back. If they couldn’t, we would model what was expected. Our lessons were 20 minutes long and followed the same class procedures as any other lesson — only they were in Hebrew. I really loved teaching those classes.

Basically, I think one of the big reasons we become what we become is because we are given the chance to excel at something and the feeling of success helps keep us interested. I wasn’t a particularly great 12-year-old Hebrew teacher, but I was in a very warm and supportive environment. I was free to make mistakes and improve. So when I got to be about 16 years old and had a chance to work at summer camp as a counselor and work at a nature center, I jumped at it. I spent the summer teaching elementary students about the life cycle of painted turtles and how to recognize about 20 kinds of edible plants, and the list of at least tangentially teacher related jobs just goes on and on. Basically, becoming an English teacher was the end result of having a chance to teach and finding out that there was something in teaching for me. It’s what happened because the people around me were encouraging and helped me succeed and take pleasure in what I was doing. That’s something I hope informs the way I teach and what I hope my students get to experience in my classroom.

What are you most interested in right now?

As a teacher, I’m most interested in making sure I have the skills I need to meet my students where they are at any given moment during the day. I know this seems kind of fuzzy, so perhaps I should give a few concrete examples. Up until a few years ago, I was not very good at teaching vocabulary, nor did I think teaching vocabulary was necessarily a good use of a teacher’s time in class. I just expected my students to spend the time necessary to build their vocabulary out of class. This was my prejudice and I carried it around as if it was a truth. But what I failed to realize was that for some students, vocabulary is their main area of interest. Or even if they are not particularly interested in vocabulary, on any given day they might suddenly be very interested in a certain lexical chain or a particular word family. And when that happens, it’s my job as a teacher to make the most out of that moment, which means I need to be able to help explore almost any language issue which my students find interesting at any given moment. That means I need to be up on my International Phonetic Alphabet. I need to know about early literacy issues. I need to be ready when my student asks me to go exploring a new space with them.

On a little more down to earth level, the big things I’ve been working on in the classroom the past few years include:

– Humanizing the standard testing procedure. I can teach to a test and perhaps even help improve students’ scores, but I decided roughly three years ago, while helping students prepare for the speaking portion of a standardized test that I had had enough of that particular mind set. Now most of the trainings I hold for the standard tests are student led, offer chances to engage in realistic conversations, and encourage as opposed to limiting personal expression. Interestingly enough, the student pass rate has gone up as well. I have an article coming out in the next issue of KOTESOL’s The English Connection and would be happy to answer questions anyone might have about how preparing for standardized tests can be turned into a richer and more positive communicative experience.

– Using literature in the classroom. There’s a lot of great material out there specifically made for the language classroom, but I think we really miss out on something important when we ignore fiction and poetry in our classroom. Language, in many respects, evolved not to just give information, but to help us tell our stories, and students really react well to stories. They get passionate about the characters. They express their dismay when things don’t go well for a particular hero. There is just a much stronger emotional connection with the material. Of course, I am really indebted to Mark Furr’s (http://www.eflliteraturecircles.com/howandwhylit.pdf) work on reading circles and Stephen Krashens stuff on extended reading, but aside from reading oriented classes, I try and use fiction in my communicative and even my study-abroad prep classes. I have tried writing a few short-short stories (under 500 words) for English language learners and have them posted on my blog. I’ve gotten some feedback that students enjoy the stories and it is very gratifying.

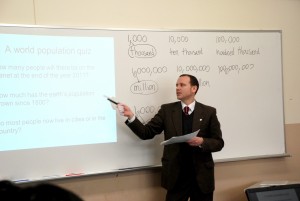

Pictogloss: probably the biggest thing I’ve been working on is an activity I call pictogloss. For the past two months, 16 second year high school students and I worked to develop a new image-based take on the dictogloss activity. The students’ feedback was spot-on and over the course of 9 weeks we really came up with an activity we all want to share with the broader ELT community. So wrote up the entire process of how the activity came to be and tried to highlight the role of the students in the activity’s development. It’s the first paper I wrote with extensive student input. Right now I’m in the process of rewriting the final draft and thinking of where I might be able to find an audience for the paper, but just the experience of actively soliciting students ideas and feedback for an academic article has been really humbling and positive.

What things do you do to help you get better at being a teacher?

I’m very lucky to work at Clark Memorial International High School. It is a network of private high schools in Japan and currently John Fanselow is our advisor on the International Course Program. A lot of my growth as a teacher just comes from the fact that John is always willing to take a moment and ask a question which I hadn’t thought about before. So no matter what type of activity I run in my class, if I film it or write it up and send it to John, I am going to be able to look at it in a totally different way after he gives me his feedback. And once again, it’s this chance to notice which really seems to help me change and grow as a teacher. But there’s only one John Fanselow and there are 14 of us teachers at the school, so I try not to use up too much of John’s time. But one thing John has pushed which I think has really forced me to improve as a teacher is simply video taping my classes. I video tape at least one class a week, pick two minutes of the lesson and transcribe it and what I find is I don’t necessarily say or do the things I think I say or do in a class. Being able to revisit my class through the impartial lens of the video camera has really helped me form a more honest and more critical view of what I do in my classes.

I also mentioned some of the teachers who support me earlier and think I need to mention again just how much the teachers who I exchange ideas with on Twitter (especially #ELTchat) are constantly providing me not only with support, but with a steady stream of questions about what I am doing in my classroom. The curiosity of the teachers I’m in contact with helps me refine how I think about what I’m doing in my class. The other day, a teacher in Korea wrote me to ask if I could provide some more insight on how some image-based dictation activities I use in class might lead to language acquisition. Which resulted in me looking back on my class notes and talking it over with my students. Which led to some small but important changes in my class procedures.

But probably the most important thing I’ve learned to do to improve as a teacher is just admit that something isn’t working out and ask for help. The fear of not being perfect and the shame of not knowing what to do can be really damaging, especially for a teacher, a person who is supposed to hold the answers. But as teachers, we need to be learners first, and that means owning up to the fact that we don’t have most of the answers, that we are in fact finding and creating them with our students and our peers from day to day and class to class. So I will often send out a tweet or write a blog post and look for help from the wider ELT community. And in a similar way, when I take part in webinars (and I really recommend webinars. Penny Ur’s take on classroom management and methodologies in the last iTDi webinar really changed how I use class time) or go to small (and free) conferences, I ask a lot of questions. I’m not over my fear of looking like I don’t know something, but I’m getting better at dealing with it.

What’s the biggest challenge you face as a teacher?

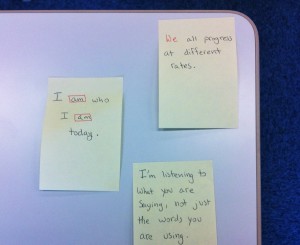

I’m facing two major issues as a teacher right now. The first is the fact that I am a really result-oriented and goal-oriented kind of person, but I am working in situation where that kind of mind-set can really get in the way of my relationship with my students. You see, I work in a school where a majority of the students have suffered from school refusal syndrome while they were in junior high school. That means that many of my students have a huge amount of anxiety when it comes to just going to school. They are also very finely tuned-in and dislike being in evaluative situations. Of course this is all at a rather impersonal level, but I see it expressed regularly in my classes. Students will miss tests regardless of how well prepared they are. They will get in a fight with one of their classmates and then be unable to bring themselves to go to school again for a week. And my, “You will get better at English, no matter what” kind of stance and attitude has sometimes made the classroom less welcoming and less safe for my students. Now the good news is that actively using reflective practices like journaling and blogging has helped me recognize this as a place where I need to spend some of my time and energy to develop. And then there are amazing blogs like Josette LeBlanc’s Throwing Back Tokens (http://tokenteach.wordpress.com/josette-leblanc/), which are focused on classroom empathy and have a different focus than the one which I bring to my classroom. nd the more I work on it, the more I realize that what I thought were issues particular to my school and my classroom are really universal issues. It’s just a question of how they play out in a particular fashion in my school. But the fact that students need to be supported, that my goals are not always a students’ particular goals, that I need to make sure I am taking notice of where my students are at emotionally today and everyday are things I would need to do to be a better teacher, regardless of where I was teaching. So I guess my biggest challenge right now Is how to be a more empathic teacher. And mostly I am working on this by journaling and blogging about my classes, twittering and sending emails back and forth with fellow teachers, trying to place what I do within the larger ELT context.

What advice would you give to a teacher just starting out on a journey of professional development?

I have two pieces of advice. Both of which I wish I had taken to heart earlier in my career. The first is that you are the best person to judge your particular situation and the needs of your students. That means trust what you see in your class, believe what your students tell you, and use that information to improve the learning environment for both you and your students whenever possible. But in order to notice what is going on, I recommend both journaling and video-taping your classes. Watch and think about what happens in your class after you have a little distance from the actual event. The other piece of advice is to do everything you can to invite the world into your class and bring your experiences out of the classroom into the world. What you are experiencing is not new. There are people who can listen and with a timely question or suggested article or story, can help you discover ways to move through any rough spots you might be experiencing. Get on twitter. Attend webinars through iTDi, TESOL Int., and any other organization which offers them. Join your voice to the voice of the ELT community. As educators you are part of a rare breed of professionals, a group of people who are striving to help each other succeed in a way other professionals can hardly imagine.

Any blog or online link you’d like to recommend?

Well, there is my own blog, The Other Things Matter: http://theotherthingsmatter.blogspot.jp/ in which I do a bit of reflective blogging on my own classes as well as how I think ELT theory can and does influence my own teaching style.

I also think that Barbara Sakamoto’s teaching Village (http://www.teachingvillage.org/) is a must stop for any teacher. There’s an amazing range of teachers’ voices and they write eloquently on the what and how of their classrooms.

There are a number of blogs I read regularly, but I would like to just highlight two more if I could. Josette LeBlanc’s blog and how it treats issues of empathy and the role of reflective practices in teaching is really a must read for anyone, not only as an example of how RP works, but as a reminder that all of us need to be kind to ourselves and accept our own experiences for the treasures they are. And then there is Scott Thornbury’s An A-Z of ELT (http://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/) I can’t say how many times I’ve been flummoxed by a certain term or idea floating around in the ELT world, only to have it take a nice crystallized shape after reading one of Scott’s blog posts.

What’s your favorite quotation about being a teacher or about education in general?

It is our job to help students realize how much they already know about language. — John Fanselow

It is our job to help students realize how much they already know about language. — John Fanselow

I think this quote really captures what it means to help meet a student where they are and together explore what the next step in learning will be about. All of our students are already, in some sense, linguistic geniuses. They can use language to express how they feel, get what they need, console a friend, and celebrate life. As a fellow member of a learning community, my job starts by recognizing and respecting what the student knows and finding a way to take the next step together.

6. Ignore general lists of things that should or shouldn’t be done for students. When talking with one another, my students have no such lists in mind. As far as I can tell, they also have no intention of making one, which seems to me to be a very good thing indeed. Watching them support, share, and relate with each other from moment to moment is the best way I’ve found to keep learning what it means to be the kind of teacher I need to be—for them and for myself.

6. Ignore general lists of things that should or shouldn’t be done for students. When talking with one another, my students have no such lists in mind. As far as I can tell, they also have no intention of making one, which seems to me to be a very good thing indeed. Watching them support, share, and relate with each other from moment to moment is the best way I’ve found to keep learning what it means to be the kind of teacher I need to be—for them and for myself. It is our job to help students realize how much they already know about language. — John Fanselow

It is our job to help students realize how much they already know about language. — John Fanselow