Towards Babelfish – The Challenge of Research

Research has changed the world and advanced our capabilities immensely. Research brings us closer to maximising our potential as humans. Most people agree that academic research on language learning and teaching is important. Understanding language and the processes that take place during and around its acquisition is fundamental to developing effective teaching and learning methods and tools.

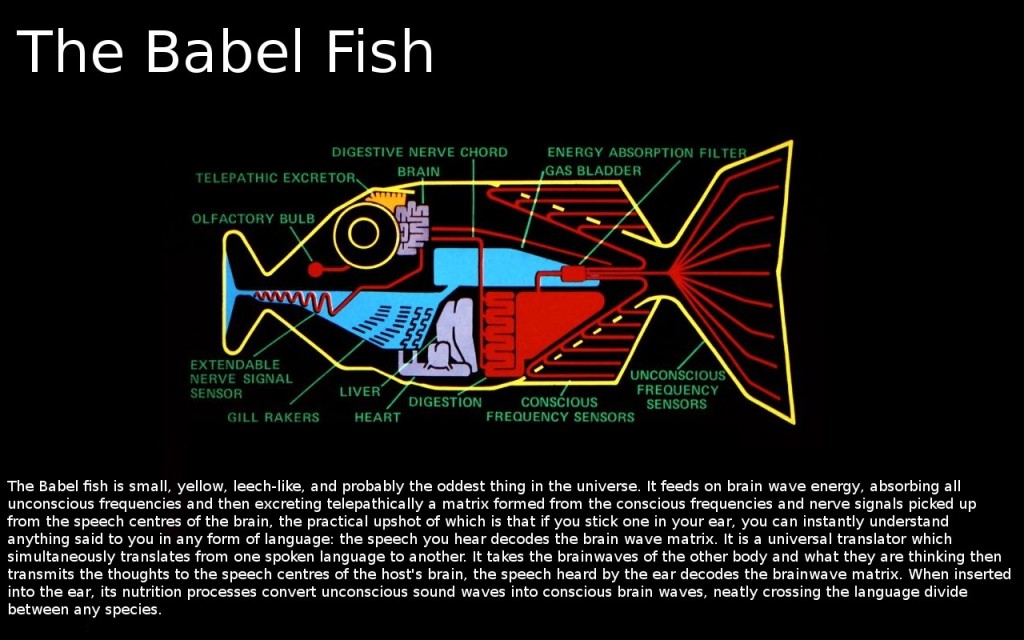

Research will eventually help us design Douglas Adams’s Babelfish, a device worn in the ear offering simultaneous translation. (Apparently, US Soldiers are already using something pretty awesome in Afghanistan. All the wonders we have the military to thank for!?)

Yet as it currently stands, most research about language learning does not serve the purposes it should.

My very naive idea about reforming research centres around three problems:

Problem 1: Academic research versus classroom-based research

Farrell quotes Sagore, who claims that despite its importance much academic research is “not necessarily helpful to teachers on the front line.” (Farrell: 95) At the same time the overall validity of research conducted by teachers in their own teaching environments is debatable and usually dismissed by the academia due to its inconsistencies. This seems to be an impasse which leaves the field of understanding language learning and teaching bereft of great opportunities for learning and discovery. The efforts of teachers tackling their day-to-day activities in the classroom and making an effort to better understand should be encouraged and acknowledged.

Tools and methods should be designed and made available that make classroom-based research more reliable and accepted by the academia.

Problem 2: Research information is scattered and uncoordinated

We pick and choose the research we use quite randomly. And we can do so because the research findings are all over the place and it takes an awful amount of investigation to identify the sources and wade through them. The complexity of each aspect we study (language, learning and teaching) make it such a vast realm that unless we provide researchers with maps, compasses and goals, they will end up going around in circles and having little understanding of what they are doing. This again leads to much irrelevant and unreliable research and missed opportunities.

Different universities have reputations for being the hotbed for certain aspects of research already. I believe it would greatly benefit the field if we had different institutions involved in studying different aspects of language acquisition to become coordinating bodies for their particular field. They could then attempt to structuralise the research available and encourage researchers to investigate certain aspects of that particular field. By establishing partnerships with international institutions, these universities would open up the possibility of research taking place in as many contexts as possible, for the benefit of as many English language teachers as possible.

Problem 3: Studies are inaccessible

One of the reasons for inaccessibility is the disparity of information I mentioned above. Another reason is financial. The costs of buying academic books or publications are prohibitive to many, and limit how much high quality research takes place. In many parts of the world libraries can’t afford the books needed even for the most basic research. This leads to even more ill-informed and unreliable “research” conducted by researchers with little or no understanding of what they are supposed to be researching.

As much of the research conducted by academics and students is funded by public bodies, the findings of that research must also remain in the public domain, and be freely available electronically so that even teachers and professors working at the most remote corners of the world have equal access to knowledge that is already available and should form the basis of further research.

This brings up my number one problem. Who benefits from all the research conducted by BA and MA students? Would it not be great if all the efforts of thousands of under- and post-graduate students could contribute to a better understanding of our discipline? What I see at the moment is thousands of trees cut down to archive works that will never be read. I don’t have a solution for this problem but I feel that the millions of hours spent on going though the same processes could be put to much better use.

Learning belongs to all. As teachers, we owe it to our students to have a solid understanding of how language is learned and how best to teach it. As citizens, we must work towards free access to knowledge so that we may give our children a more promising future, and finally install that device in our ears that will render our language teaching jobs obsolete.

Credit: NoSalt

Bibliography

Farrell, T (2007): Reflective Language Teaching – From Research To Practice Continuum, London