The Obvious Can Be Difficult To See — John F. Fanselow

. . . the obvious can be very difficult for people to see.

(Bateson, 1972, p. 429)

Why? According to Bateson, it is because “. . . people are self-corrective systems. They are self-corrective against disturbance, and if the obvious is not of a kind that they can easily assimilate without internal disturbance, their self-corrective mechanisms work to sidetrack it.”

I illustrate the theme with his sorting activity. Write down which stamps below contain these categories:

Sources of heat

Women

Water

Non-English

I have asked hundreds of people to sort the 4 stamps using their own categories. Hardly any used four categories I asked you to use. Even with Non-English as a label, few wrote Olympiad, XIII or Los Angeles in stamp 1 or Graf Zeppelin in stamp 3 or Pocahontas in 4. The torches in 1 and the engines in 3 were rarely seen. It usually takes quite a bit of time to notice the clouds and the globe showing the oceans in 1 and 3.

We are used to looking at denominations, country and maybe the date on stamps. Knowing that the first stamp has torches is not particularly important information. Obviously Lincoln is the focus of the second stamp and not the two women engraved on the sides as decoration.

What I just asked you to do with the stamps is central to the understanding of our teaching.

1. By using labels to highlight features that are not obvious, you had to analyze. Of course in looking at your teaching you should use labels you are familiar with initially. Ones I often hear include these:

off task on task

teacher talk student talk

clear explanation

unclear explanation

But as you look at samples of your teaching, with students and colleagues if possible, you will all create new labels: necks straight, students using erasers every time I say “Mistakes are OK”, using their first language to clarify what I am doing or to chat. The more original and the less use of jargon from methods books the better.

2. I asked you to look at a small amount of data in different ways. If you transcribe a recording that fills one A4 sheet of paper, it will be enough data to see something new about what you and your students are doing. The point is to look at a small amount of data from multiple perspectives rather than to look at a lot of data from one perspective.

3. Some make judgments like “Ugly design, boring color” in the process of sorting stamps. Judgments are very, very common when teachers first hear what they say and their students do. “Wow, I talk too much; some students wrote too slowly.” I used to encourage teachers not to judge but advocate writing judgments down. Then, look for examples in the recording and transcription that support the judgments and do not support their judgments. And then write ways that what you initially think is negative—like students writing slowly—might be positive. As teachers consider how talking a lot might be helpful some have asked their students to transcribe their talk. They realize that much of what they say is natural but that in fact students do not understand them. As they transcribe and practice teachers’ language, they improve their listening and master many of the patterns.

I am not suggesting that you should not vary the amount of talk but rather to see how what we initially think is positive or negative can in fact be the opposite.

4. I urge you to spend fifteen minutes twice a week. This adds up to a lot of time in a term but one purpose of the analysis is to plan a change in your teaching so transcribing and analyzing becomes planning time.

634 Words

Grade Level 8.3

Flesch Reading Ease 65%

Connect with John, Chuck, Ratnavathy, Chiew, Josette, Kevin and other iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.

The beauty of questioning is that it helps you look deeper into yourself. Questions ask you to investigate, to doubt, to grow, and to change. Questions help you learn to see.

The beauty of questioning is that it helps you look deeper into yourself. Questions ask you to investigate, to doubt, to grow, and to change. Questions help you learn to see.

For several years, I’d finish classes and head to Ginza to wander the streets. I can honestly say that I’ve never been lost in Ginza– until this morning.

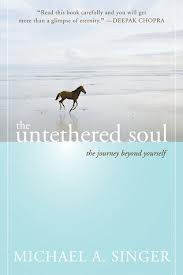

For several years, I’d finish classes and head to Ginza to wander the streets. I can honestly say that I’ve never been lost in Ginza– until this morning. I’m reading a book called The Untethered Soul by Michael A. Singer. In this book, Singer writes about the voice inside all of us, about how that voice can get us to believe it is who we are and is reality itself. It’s not. “What voice?” I can hear you asking. Say the word “hello” silently in your mind. Make your inner voice say “hello” several times. Hear that? That voice. Make it shout “hello” inside yourself. Make it say, “I’m not good at ______.” No, stop. Don’t complete that sentence. Make the voice say, “I’m really good at ______. Complete the sentence in different ways. Listen to yourself. Now, think about this.

I’m reading a book called The Untethered Soul by Michael A. Singer. In this book, Singer writes about the voice inside all of us, about how that voice can get us to believe it is who we are and is reality itself. It’s not. “What voice?” I can hear you asking. Say the word “hello” silently in your mind. Make your inner voice say “hello” several times. Hear that? That voice. Make it shout “hello” inside yourself. Make it say, “I’m not good at ______.” No, stop. Don’t complete that sentence. Make the voice say, “I’m really good at ______. Complete the sentence in different ways. Listen to yourself. Now, think about this.