Doing and Being: How Mike Rolls Michael Griffin

Doing and Being: How Mike Rolls Michael Griffin

As an enthusiastic rule finder, bender, breaker and scoffer it was interesting and hopefully useful for me to think about which rules I always try to follow. For other teachers reading this who are allergic to rules being imposed on them (like me), I must mention that these are not rules I am suggesting you follow but just sharing rules that I choose to follow for myself.

As an enthusiastic rule finder, bender, breaker and scoffer it was interesting and hopefully useful for me to think about which rules I always try to follow. For other teachers reading this who are allergic to rules being imposed on them (like me), I must mention that these are not rules I am suggesting you follow but just sharing rules that I choose to follow for myself.

Be on time

I like to start class on time, every time. I think it is more efficient to make sure we all know when class is going to start and to do so. Starting on time one of the easiest things for teachers to control but is something that can be overlooked or forgotten. I feel the teacher starting on time is a good model for students and I don’t think we can expect students to be on time if we are not.

Be prepared

In this case, I don’t mean that I need to have mountains of handouts, all my teacher talk clearly written out, or a minute-by-minute breakdown of what I am hoping will be done in each moment of the class (though I have surely had all of these things at various times in the past). I simply mean I must have a few different ideas about different activities we might do in class while always keeping the overall goals and objectives of the course in mind. As much as I sometimes enjoy and feel comfortable “winging-it” I can’t imagine going to class without at least a few options and ideas.

Be flexible

Sometimes, regardless of how well-prepared we believe ourselves to be, we need to stray from the plan. At various times in my teaching career, I have pushed the plan or materials that I toiled over the night before too hard and have realized being stubborn about using the plan or materials is not productive for me or my students. It’s always important to keep in mind that my job is to teach the students not the plan or the material.

Be aware of students

It can sometimes be easy to forget about students as we focus on “covering” material. My personal rule is to always try to think about the students as I plan and teach especially in terms of abilities, personalities, needs, interests, and current mood and situation.

Be yourself

It is becoming more and more apparent to me how important being myself in class is to me. Part of this is because I have realized I am not so good at being anyone else and the other part is that students seem to respond to the “real me” better than any fake version of myself I might create. Being myself in this sense includes but is not limited to giving my real opinion (especially when asked), joking around, showing care for students’ lives outside of class, telling the truth, disclosing personal information when comfortable, and at times choosing not to disclose personal information.

Be positive

This is easier said than done sometimes but I think it is important for me to remember (especially on down days) how much I love my job and why I choose to do this kind of work. Thinking of this usually cheers me up, or at least helps me focus on the job at hand.

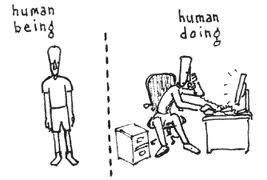

As I wrote this list I realized that a lot of my rules are things to be rather than things to do. Perhaps this shows that for me a lot of teaching is more about being than doing.

As I wrote this list I realized that a lot of my rules are things to be rather than things to do. Perhaps this shows that for me a lot of teaching is more about being than doing.

Malu’s One Rule – Malu Sciamarelli

Malu’s One Rule – Malu Sciamarelli

I’m not a terribly consistent rule follower, I’ve discovered. There are, however, two rules about teaching that I have been pretty good about keeping. They are:

I’m not a terribly consistent rule follower, I’ve discovered. There are, however, two rules about teaching that I have been pretty good about keeping. They are: For example, the idea that teachers should incorporate techniques to reach different learning styles or multiple intelligences has been largely discredited in research studies. Not only is there no proof that teaching to different modalities is useful, there is evidence that it can be counter-productive. However, thinking in terms of learning styles is still a useful rubric for lesson planning, and getting teachers to see that they tend to teach in the way that they like to learn is a valuable step in encouraging them to experiment with different ways of presenting material. For many teachers, the idea that the same material can be taught in a variety of ways is new, and liberating. The idea that students process information in different ways resonates with teachers.

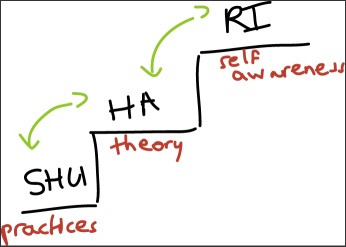

For example, the idea that teachers should incorporate techniques to reach different learning styles or multiple intelligences has been largely discredited in research studies. Not only is there no proof that teaching to different modalities is useful, there is evidence that it can be counter-productive. However, thinking in terms of learning styles is still a useful rubric for lesson planning, and getting teachers to see that they tend to teach in the way that they like to learn is a valuable step in encouraging them to experiment with different ways of presenting material. For many teachers, the idea that the same material can be taught in a variety of ways is new, and liberating. The idea that students process information in different ways resonates with teachers. Do I think all teachers should use learning styles as a rubric for planning lessons? Do I think all teachers should use rewards? No, of course not. What works with one of my classes may not even work with another of my classes, let alone another teacher’s class. Each group of students has its own dynamic, and requires a slightly different teaching style.

Do I think all teachers should use learning styles as a rubric for planning lessons? Do I think all teachers should use rewards? No, of course not. What works with one of my classes may not even work with another of my classes, let alone another teacher’s class. Each group of students has its own dynamic, and requires a slightly different teaching style.

A rule, law, or regulation is a prescribed guide for action. That could be the definition you can get from any dictionary. For me, a rule is something that you try to keep in mind as a line that shouldn’t be crossed — unless it is unavoidable.

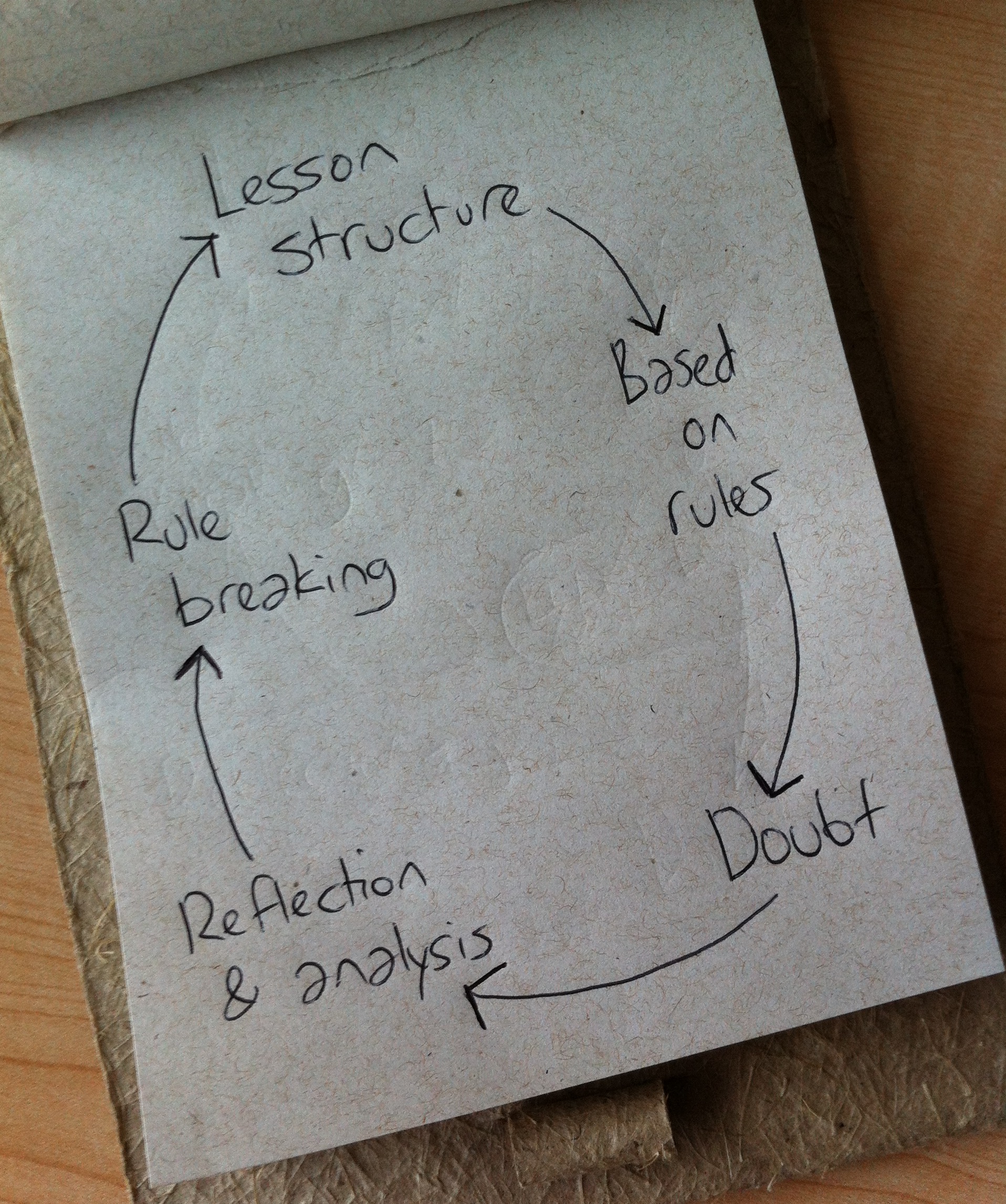

A rule, law, or regulation is a prescribed guide for action. That could be the definition you can get from any dictionary. For me, a rule is something that you try to keep in mind as a line that shouldn’t be crossed — unless it is unavoidable. Whether we’re talking about rules from the first or the second group of rules, over time we may find ourselves questioning them and may find them unsuitable for the present situation. That is the moment we can be called rule-breakers, inconsiderate or even insane. That is the moment we look for change and a way to overcome a present situation that no longer allows us to grow. That’s when we change.

Whether we’re talking about rules from the first or the second group of rules, over time we may find ourselves questioning them and may find them unsuitable for the present situation. That is the moment we can be called rule-breakers, inconsiderate or even insane. That is the moment we look for change and a way to overcome a present situation that no longer allows us to grow. That’s when we change. Unbreakable Rules of @TheTeacherJames – James Taylor

Unbreakable Rules of @TheTeacherJames – James Taylor