by Kevin Stein

by Kevin Stein

For me, I’ve found my release in poetry. On the crowded train ride home, I will often open a book of Tanka, traditional Japanese short poetry, and so lose myself in the small gem of a moment captured in five lines. I will worry over these poems the same way a small child might rub a shiny, smooth stone. And every once in a while I will try to write poetry as well.

Poetry, it’s how I ended up in an unexpected conversation (as online conversations so often are) with a poet and English teacher in India, Tesal K. Sangma. At first we did not talk about teaching, but about our love for traditional poetry forms. Tesal sent me a poem, Soul Bird by Temsula Ao. It was the kind of poem that left me feeling I had traveled for hundreds of miles over the course of less than a page. Slowly our conversation moved from poetry to our classroom experiences. Tesal was required to teach poetry in his classes, but he was having difficulty finding poetry that his students could understand and identify with. At the same time, I was doing a tanka translation project with my students, but they had no audience with whom to share their poems.

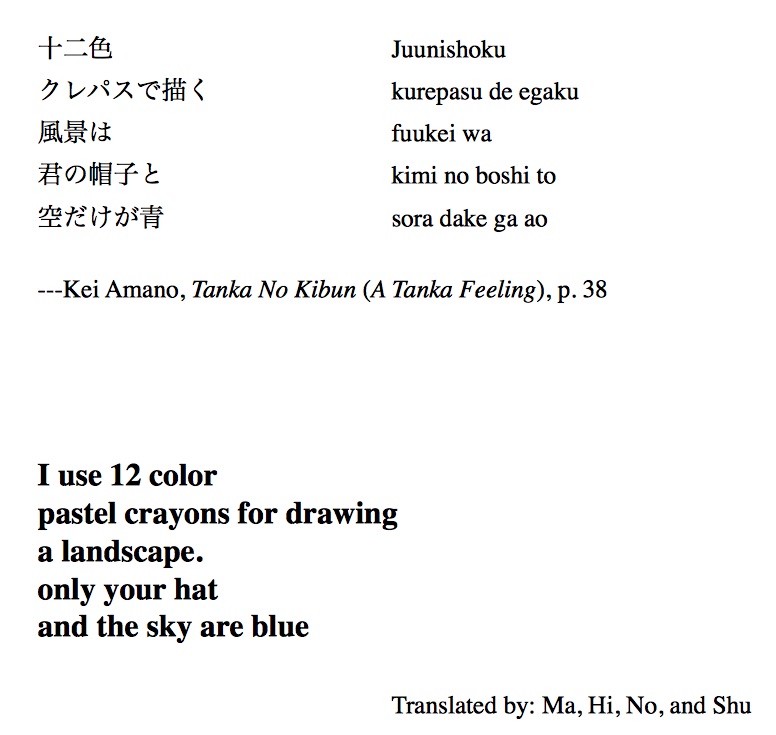

This is all we had to start with, just the idea of one group of students translating traditional poetry from their first language into English to be used by another group of students studying literature. As I explained the idea to my students, one boy, P-Kun, looked at the poem about pastel crayons he and his group had been struggling over, and added the following line at the bottom of the page, “From children to adults, many people use pastel crayons to draw pictures in Japan.” He explained that he was worried that the students in India would read the word crayon and imagine that the narrator was a child. Soon after, all of the other groups had added culture footnotes to their poems. We sent the poems and cultural footnotes off to Tesal to share with his students. And Tesal took pictures of his students, huddled over their desks, pencils in hands, reading over the poems that my students had translated. When I shared these pictures with my students, there was a moment of silence, a kind of muffled cloud of disbelief. When one of my students, H-Chan, asked the question that anyone would ask in such a situation, “What did they think about the poems?” It was in this moment of true curiosity of how my students’ language had affected someone 5000 kilometres away, that the poetry they were writing became part of a larger conversation firmly embedded in their own lives.

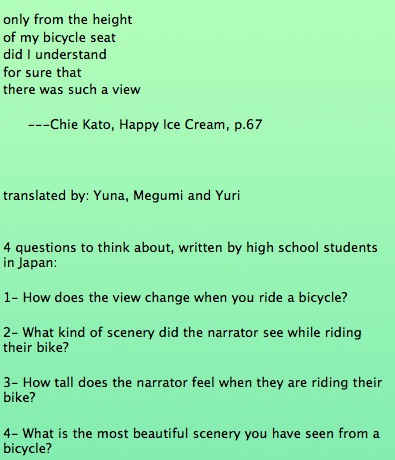

My students spent a solid hour writing out questions for the students in India.

These were questions that showed flashes of critical insight into the structure and nature of poetry. Did the students in India think that the narrator of a certain poem was a boy or a girl? Was the poem’s tone hopeful or sad? Their questions also moved beyond the small frame of the poem itself. My students used the poems to ask questions about the lives of the students in India. Questions like, “What is the most beautiful scenery you’ve ever seen from a bicycle?” and “Do high school students in India have boyfriends and girlfriends?” I worked with my students to build a Lino Board and it was through this interactive medium that the students in India and Japan continued their conversation. In the end, my students decided to collect all the stages of this project into a book, Exchange Through Tanka Project.

“Find something you are passionate about outside of teaching.” It’s some great advice. I would add a caveat to it. “Find something you are passionate about outside of teaching, but don’t be afraid to bring that passion into your classroom.” Don’t be afraid to let your passion connect you to other teachers and to your students. Because it is within the soil of that shared passion that collaboration begins. Successful collaboration is not simply about engaging with others. In the end, collaboration is about creating the very ground beneath our feet as we walk together on a completely new path.

[This post is dedicated to the students in the Bachelor of Social Work programme at Martin Luther Christian University in Meghalaya, India who inspired my students to think deeper, ask questions, and search for the personal meaning in the poetry around them.]

[This post is dedicated to the students in the Bachelor of Social Work programme at Martin Luther Christian University in Meghalaya, India who inspired my students to think deeper, ask questions, and search for the personal meaning in the poetry around them.]