I’m not a terribly consistent rule follower, I’ve discovered. There are, however, two rules about teaching that I have been pretty good about keeping. They are:

I’m not a terribly consistent rule follower, I’ve discovered. There are, however, two rules about teaching that I have been pretty good about keeping. They are:

1. Learn as much as possible about as many things as possible so that I have a large pool of resources to draw from in teaching.

2. Don’t let what I learn interfere with what I know is right for my students.

The first rule has helped me rationalize learning about any number of things — from trivia about the animal kingdom as a way of providing a context for learning English to technology tools as a way of teaching.

The second rule keeps me grounded. I try to stay current with research about teaching and learning, and I appreciate educators who conduct studies to evaluate how and why things work (and don’t work) in the classroom. There’s value in research. However, there’s also a risk in adopting or dropping something I do in class simply because it is or is not validated by research.

For example, the idea that teachers should incorporate techniques to reach different learning styles or multiple intelligences has been largely discredited in research studies. Not only is there no proof that teaching to different modalities is useful, there is evidence that it can be counter-productive. However, thinking in terms of learning styles is still a useful rubric for lesson planning, and getting teachers to see that they tend to teach in the way that they like to learn is a valuable step in encouraging them to experiment with different ways of presenting material. For many teachers, the idea that the same material can be taught in a variety of ways is new, and liberating. The idea that students process information in different ways resonates with teachers.

For example, the idea that teachers should incorporate techniques to reach different learning styles or multiple intelligences has been largely discredited in research studies. Not only is there no proof that teaching to different modalities is useful, there is evidence that it can be counter-productive. However, thinking in terms of learning styles is still a useful rubric for lesson planning, and getting teachers to see that they tend to teach in the way that they like to learn is a valuable step in encouraging them to experiment with different ways of presenting material. For many teachers, the idea that the same material can be taught in a variety of ways is new, and liberating. The idea that students process information in different ways resonates with teachers.

So, even though learning styles are “so last year” in research circles, I still use them as a way to make sure my lesson plan is multisensory, and include them in teacher training because they are a useful way of looking at what happens in our classrooms.

Interestingly, cognitive scientists now suggest that rather than teaching in a way that suits our students, we should teach in the way that best matches our lesson content (e.g., learning to play soccer is probably best done by kicking a ball on a soccer field rather than by listening to someone talk about playing soccer). Learning a language involves multiple senses, so essentially we follow a different path to the same destination. We should teach in a multi-sensory way not because our students have learning style preferences but because it’s the approach that best suits teaching language.

Rewards are another example of me choosing to ignore what I’ve learned in favor of what is right for my students. A quick Google search shows many reasons why rewards are a bad idea — students get addicted, they won’t develop intrinsic motivation, and eventually the rewards stop working. However the majority of articles refer to teaching contexts very different from my own. I see students once a week, and English is simply one of many after school classes children participate in. The chance to choose a sticker means that homework is usually done (and shown and checked within minutes of entering the classroom door). Younger siblings get a sticker at the end of class if they’ve been able to follow class rules for the entire hour. There’s no penalty if homework doesn’t get done or younger siblings have an off day, but there is a small reward for compliance. Typically, students start forgetting about taking a sticker in about third grade, and are pretty autonomous homework-doers by the time they hit 4th grade.

Do I think all teachers should use learning styles as a rubric for planning lessons? Do I think all teachers should use rewards? No, of course not. What works with one of my classes may not even work with another of my classes, let alone another teacher’s class. Each group of students has its own dynamic, and requires a slightly different teaching style.

Do I think all teachers should use learning styles as a rubric for planning lessons? Do I think all teachers should use rewards? No, of course not. What works with one of my classes may not even work with another of my classes, let alone another teacher’s class. Each group of students has its own dynamic, and requires a slightly different teaching style.

I think that teachers need to learn as much as possible about as many things as possible so that we can make informed choices about how to teach the students in our classrooms. The longer we teach, and the more we learn, the more confident we can become about making the choices we do, regardless of what research says is “right.” Ultimately, no one knows as much about our own students and their needs as we do.

If you’d like to do a bit of reading about learning styles and rewards, here are a few articles to get you started:

Don’t teach to learning styles and multiple intelligences [http://penningtonpublishing.com/blog/tag/vak/]

Do Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Learners Need Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Instruction? [http://www.aft.org/newspubs/periodicals/ae/summer2005/willingham.cfm]

The Risks of Rewards

[http://www.alfiekohn.org/teaching/ror.htm]

Six Reasons Rewards Don’t Work

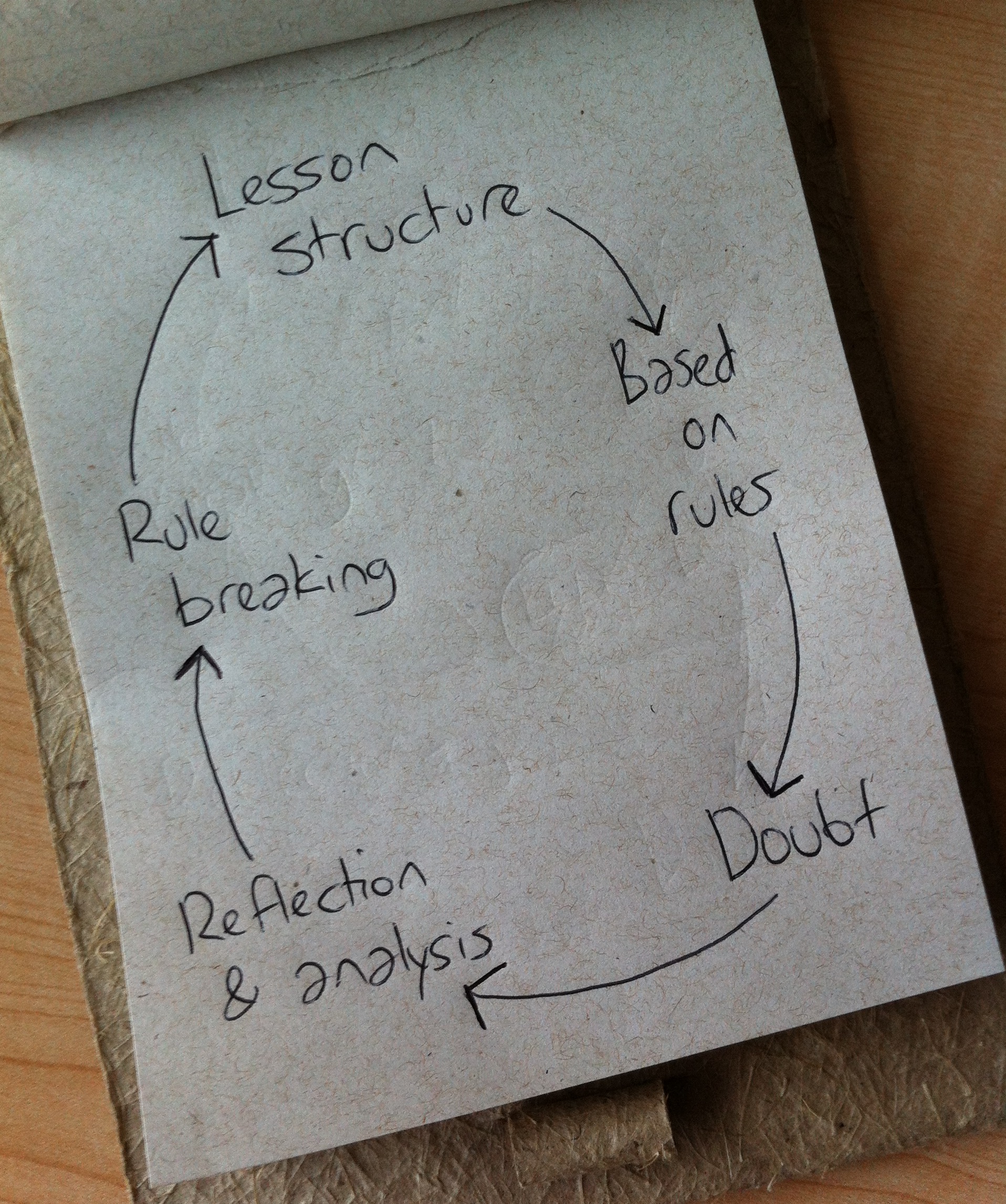

A rule, law, or regulation is a prescribed guide for action. That could be the definition you can get from any dictionary. For me, a rule is something that you try to keep in mind as a line that shouldn’t be crossed — unless it is unavoidable.

A rule, law, or regulation is a prescribed guide for action. That could be the definition you can get from any dictionary. For me, a rule is something that you try to keep in mind as a line that shouldn’t be crossed — unless it is unavoidable. Whether we’re talking about rules from the first or the second group of rules, over time we may find ourselves questioning them and may find them unsuitable for the present situation. That is the moment we can be called rule-breakers, inconsiderate or even insane. That is the moment we look for change and a way to overcome a present situation that no longer allows us to grow. That’s when we change.

Whether we’re talking about rules from the first or the second group of rules, over time we may find ourselves questioning them and may find them unsuitable for the present situation. That is the moment we can be called rule-breakers, inconsiderate or even insane. That is the moment we look for change and a way to overcome a present situation that no longer allows us to grow. That’s when we change. Unbreakable Rules of @TheTeacherJames – James Taylor

Unbreakable Rules of @TheTeacherJames – James Taylor